by Martin Willis

This editorial is about American furniture, I may write at a later time explaining how to tell the difference between Period American and English Georgian furniture of the same era. When I speak of period furniture, I am referring to pieces that are considered traditional styles of design constructed in the Colonial through Federal era, between 1730-1810 such as Queen Anne, Chippendale, Sheraton, Hepplewhite, Duncan Phyfe and Federal furniture. Following this era was American Empire 1815-1835 , then Victorian 1837-1901 of which machine made furniture began in 1840.

Centennial furniture was born in the traditions mentioned above debuting at the 1876 International Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. There was a nostalgia for the developing years of our country and the pieces became in high demand. This was in the midst of the Victorian Renaissance Revival styles mostly of walnut adorning the homes and parlors of the nation.

After the Centennial era, Colonial through Federal styles have had many revivals up to the present day.

Let’s start out by talking about a side-by-side comparison of a Sheraton two drawer work table.

They made a vast amount of Federal Era Hepplewhite and Sheraton style side tables. Yet they made even more Centennial era and later pieces in the same styles. Side by side in a home, even after many years, I can sometimes not tell the difference until I closely examine the piece. Like most furniture, it is the underside that tells the truth. What you are looking for is handcrafting and age compared to machine made with less age.

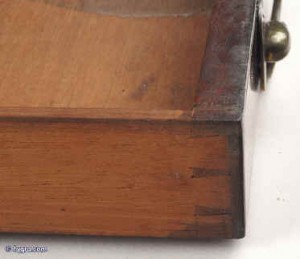

Before you tip the table upside down, pull out one of the drawers and turn it over. On a period piece, you should see what is called a chamfered edge. It is a thick board planed to a wedge that fits in the bottom slots of the drawer. Now you want to look at the dovetail edge of the drawer. The best thing I can do is show you images of both machine dovetailing (which is uniform) and hand dovetailing. Note: click any image to enlarge.

On hand dovetailing, often you see the marking scores that were used to lay the dovetailing out. Not only is construction a good way to tell a period piece, but also there should be age oxidation. Over time wood develops a dark natural look, mostly where it is exposed to air. I have seen an early high chest that had poplar secondary wood with very little oxidation where the drawers had dust divider panels, so there are exceptions. It made me suspicious and keep in mind being suspicious is a good thing when examining pieces. I always think guilty until proven innocent.

Now take the table, and turn it upside down, preferably on a carpet or blanket. You should see areas of oxidation. The inside the top should be attached by screws. Take a flashlight and look to see if the screw countersink holes appear to be made by hand with a chisel or machine drilled. Now look at the screw heads inside the holes, in particular the slots. If the slots are not perfect in the center, you have a good shot it may be a period piece.

A Centennial piece (and later) will have machine drilled countersunk holes and screw that are slotted perfect on center.

If you have an early table with turned legs, grasp one and turn your hand slowly back and forth. You should be able to feel a slight oval shape. Wood shrinks over time across the grain. Centennial and later pieces have much rounder turnings than period pieces.

I always look at the bottoms of feet on pieces to look at age as well. It is hard to explain what I am looking for other then wear and age.

You will never see band saw work on a period piece and you will rarely see perfect uniformity of construction on the underside of a period piece.

I will offer another tip a little off track to this subject. If you are convinced you are looking at a period chest on chest, or any two-part piece, you want to make sure the two parts belong together and were not “married”. Two ways to tell are, make sure the backboards are matching (color and tooling) and then stand to the side of the piece.

Pull a drawer from the top section and one from the lower section. Make a close examination to make sure the dovetail work matches on the two drawers. If either the backs or drawers look suspiciously non-matching, you probably have a married piece.

If you are not a seasoned expert, there is no sure fired way while examining pieces for you to be certain, these are just helpful tips I have learned along the way.

We have been getting a lot of email these days and have enjoyed helping people identify antique objects & art. Feel free to send us images of your pieces.

EMAIL US

Happy hunting!

Pingback: How to Discern Period Antique Furniture vs Centennial or Later

Pingback: Antique News - The very best antiques in Springfield Mo. and antique stores in Springfield, MO. - Springfield MO Antiques