I always seem to talk about fakes and reproductions in every podcast that I do. And lately I have been apologizing for doing so. Fakes have always been around and it probably always will be around. As a collector, auctioneer, and dealer I realize that there is nothing that I can do about this. The only thing I attempt to do about this is talk about it my podcast and try to get the information from each specialists in their field, specifically on how the novice and stay away from purchasing a fake by accident.

I’ve heard since a very young age, that the Chinese have been faking ceramics for thousands of years. This phrase does sound rather humorous but I’m sure it’s true. I am not picking on the Chinese specifically, it’s just that this is a good example to explain that takes a been around forever. That being said, I’d love to find 1000-year-old Chinese fake porcelain of an earlier time.

From what I can figure out in the 40 years or so that it in doing this is that if something has value, then you’ll see fakes. Sometimes the things that you see are faked are only worth a few dollars, and it is puzzling to me on why it would be worth all the effort.

A number of times someone has asked me what is the difference between a fake and a reproduction. My answer is, he reproduction is a copy of something, and a fake is a deliberate copy to deceive someone. My own opinion is I really don’t like reproductions, but I can live with them. I despise fakes because I think it hurts the markets in many ways.

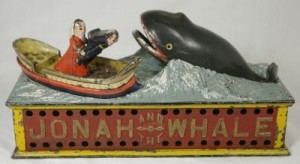

Here is a breakdown of how I think fakes and reproductions hurt the market. A quick example is if a novice collector sees something that he would like to collect but doesn’t have a thorough knowledge of it, he may search for an item and buy a fake or reproduction by accident. Here is an example; Joe remembers his great uncle had a mechanical bank that he used to play with as a young boy, he recently saw one on the Antiques Roadshow, and it reminded him of it. A few days after the show he decided that he was going to try to find one similar to what his great uncle had, which was Jonah and the Whale. Joe starts calling antique shops and nobody seems to have one, then one of the antique dealers says that he knows a friend who owns one, but the cost is pricey over $2000. Joe gets discouraged and decides he will start looking online. He ends up finding one that’s a great deal it’s only $300, so it makes the purchase. A little time goes by and Joe receives the bank in the mail it opens the box and looks perfect. It is just like he remembers as a young child. Now he’s all excited and decides he wants to collect more banks. He decides to bring the bank to the antique dealer that told him about the other Jonah and the Whale bank. He brings it to store, shows it to the dealer and to his dismay the dealer says the bank is a fake. Now Joe no longer wants to collect, he does not know who to trust, and decides to never buy another bank. To me this is a typical thing of what can happen and I’ve heard similar stories many times throughout my years.

Here is a breakdown of how I think fakes and reproductions hurt the market. A quick example is if a novice collector sees something that he would like to collect but doesn’t have a thorough knowledge of it, he may search for an item and buy a fake or reproduction by accident. Here is an example; Joe remembers his great uncle had a mechanical bank that he used to play with as a young boy, he recently saw one on the Antiques Roadshow, and it reminded him of it. A few days after the show he decided that he was going to try to find one similar to what his great uncle had, which was Jonah and the Whale. Joe starts calling antique shops and nobody seems to have one, then one of the antique dealers says that he knows a friend who owns one, but the cost is pricey over $2000. Joe gets discouraged and decides he will start looking online. He ends up finding one that’s a great deal it’s only $300, so it makes the purchase. A little time goes by and Joe receives the bank in the mail it opens the box and looks perfect. It is just like he remembers as a young child. Now he’s all excited and decides he wants to collect more banks. He decides to bring the bank to the antique dealer that told him about the other Jonah and the Whale bank. He brings it to store, shows it to the dealer and to his dismay the dealer says the bank is a fake. Now Joe no longer wants to collect, he does not know who to trust, and decides to never buy another bank. To me this is a typical thing of what can happen and I’ve heard similar stories many times throughout my years.

Now as far as reproductions hurting the market, what happens is here is a rare item no longer becomes rare. What I mean by this is that a rare item can seem abundant even though it really isn’t. A very good example of this is Galle glass. There are thousands and thousands of fake and reproduction Galle glass on the market. Some pieces are so difficult to tell between real and fake, that only an expert in the field can tell the difference. I recently spoke with Phil Chasen about Galle glass and he said he can tell a fake across the room. After 40 years of being in this business, I cannot sometimes, and that is why I think it is important to get a specialists help while purchasing pieces like this. Phil Chasen has a very informative website on Galle and other pieces, you can visit his website here.

Another example is tortoise shell tea caddies. These were mostly made in England in the early 19th century and there are some wonderful forms. They generally cost $1,000 to $3,000 depending on condition and the quality of the individual piece. What crafty fakers are doing now is buying mahogany tea caddies for a $100 or so, photo copying tortoise shell and laying down the photo-copy with glue, then lacquering them over. These look so authentic that it is unbelievable. You can buy as many as you want for $300 each.

When I think of the word “reproduction”, I often think of things that are remade in the earlier traditions. For instance, Centennial furniture in the style of traditional Colonial & Federal, a trend which started at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 (The World’s Fair). Sometimes you have to turn a piece upside down and examine it before you can determine it is Centennial instead of a piece made in the period. There are always clues as Centennial pieces may be hand carved, but the joinery is later and can easily be determined. I can certainly appreciate reproductions as often there is exquisite craftsmanship.

When I think of the word “reproduction”, I often think of things that are remade in the earlier traditions. For instance, Centennial furniture in the style of traditional Colonial & Federal, a trend which started at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 (The World’s Fair). Sometimes you have to turn a piece upside down and examine it before you can determine it is Centennial instead of a piece made in the period. There are always clues as Centennial pieces may be hand carved, but the joinery is later and can easily be determined. I can certainly appreciate reproductions as often there is exquisite craftsmanship.

I like what major art authenticators do while representing the artist’s estate. If a fake comes in for evaluation or authentication and they are certain it is not right, they destroy it on the spot.

I could go on and on about this subject, but let me make something clear. I hate fakes, I hate them with a passion. If you happen to be reading this and you are a maker of fakes, I do not like you one bit. I realize fakes have been around forever, and there is no way to stop them. If you buy one by accident, I am sorry, and all I can say is make a stink about it, drive the seller crazy until you get your money back. Fakes are part of the reason that this business suffers.

If you are selling pieces in an antique shop or auction that are fake or reproduction, do us all a favor note it as such. I know a lot of people out there do this already, and I appreciate that. We have to be a self policing business.

Thank you for reading,

Martin