An Informative Narrative by Phelps Fullerton

Our Podcast with Phelps on the subject: Click Here

I think to get a better understanding of the antique advertising market you need to get some background on how product branding came about, and some insight into the actual processes used to produce the advertising signs themselves.

So I’ll start off by briefly mentioning some background on product branding.

Branding

After the Civil War, companies that manufactured everything from tobacco to soap and flour to shoe polish began to see branding their products as a way to increase sales. A national consumer base could now be accessed by expanding train routes that offered low cost transportation. The transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869 and provided a vital link for commerce, trade and travel between the East and West. No longer did merchandise have to be shipped by boat or wagon.

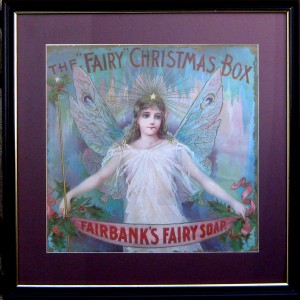

Factories created during the industrial revolution were now mass-producing products and by branding their products with easily identifiable trade-marks, they were able to make them stand out from the competition. Consumers gained confidence that product quality could be expected to remain the same from one box of Fairbanks “Fairy Soap” to the next for example.

Factories created during the industrial revolution were now mass-producing products and by branding their products with easily identifiable trade-marks, they were able to make them stand out from the competition. Consumers gained confidence that product quality could be expected to remain the same from one box of Fairbanks “Fairy Soap” to the next for example.

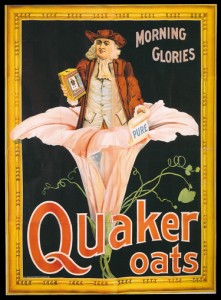

The idea of pre-packaging products in boxes of similar size, weight and price was a leap in marketing strategy from the bulk bins of the general store. It was Henry Crowell president of the American Cereal Co. that eventually came up with the concept. He bought the bankrupt Quaker Mill in 1881 and in the process acquired the registered Quaker Oats trademark described in the 1877 U.S. patent office registration as “a figure of a man in Quaker garb”. The next year he launched an all-out advertising campaign using the trademark jovial Quaker gent to promote his Quaker Oats cereal line. The concept quickly gained popularity among consumers.

An interesting aside – some 18 years ago I consulted for an auction house that was consigned a fabulous advertising poster from Quaker Oats. It was a fanciful image printed as an 8-sheet stone lithograph ca. 1890’s that featured the Quaker Oats man emerging from a gigantic pink morning glory holding a box of oats. It had a gold border printed to simulate an ogee gilt frame. Just awesome- and huge. At 7’ wide x 9’ tall it would have been intended to be pasted outdoors on the side of a building. I thought at the time it was very likely the only copy to have survived intact.

I contacted Quaker Oats thinking that this would be a remarkable piece to hang in their corporate offices, but nobody there that I spoke with had the slightest interest in it. A shame really. But it put my fascination with early advertising signs into perspective at the time, as I realized there was a slim group of folks similarly intrigued with them as I was. (Recently I’ve notice giclee reproductions of it on-line.)

Some of the more memorable trademarks that connected consumers to the product include:

1. Aunt Jemima pancake flour – the Davis Mill Co. of St. Joseph, MO had a booth at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. They hired a well-known pancake cook by the name of Nancy Green to cook and serve pancakes to the Expo attendees. I read somewhere that she served about a million of them. She was dressed in traditional southern garb and made such a personable impression that she became the “Aunt Jemima” spokesperson. In 1917 the Aunt Jemima advertising logo was revised in her likeness.

2. Buster Brown Shoes – John Bush of the Brown Shoe Co. in St. Louis, MO (named after the founder George Brown and not “Buster”) bought the rights to the popular Buster Brown comic strip drawn by Richard Fenton Outcault. The Buster Brown brand shoes made their debut at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, now endorsed by the Buster Brown caricature and his dog Tige.

2. Buster Brown Shoes – John Bush of the Brown Shoe Co. in St. Louis, MO (named after the founder George Brown and not “Buster”) bought the rights to the popular Buster Brown comic strip drawn by Richard Fenton Outcault. The Buster Brown brand shoes made their debut at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, now endorsed by the Buster Brown caricature and his dog Tige.

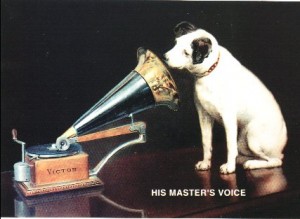

3. RCA (Radio Corporation of America) “Nipper” – London artist Francis Berroud saw his fox terrier “Nipper” looking into the horn of a Gramophone which inspired him to re-create the scene in a painting titled “His Master’s Voice”. Nipper became the trademark for the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1901 which was laterpurchased by RCA during the Great Depression.

4. Planters Nut & Chocolate Co. – the company was founded in 1906, but the monocled

Mr. Peanut wasn’t used until 1916 after a 13 year old girl came up with the idea in a company sponsored competition.

5. Heinz Pickle – Henry Heinz was 16 yrs. old when he began selling vegetables to Pittsburg grocers. His 1st business venture selling bottled horseradish went bankrupt, but in 1876 he had successfully launched a new business venture introducing bottled pickles and ketchup. The Heinz pickle was featured on much of their early advertising, and later he introduced the “Heinz 57 Varieties” trademark that remains today.

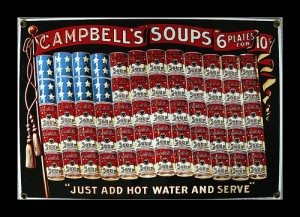

6. Campbell’s Soup – in 1897 a chemist at the Joseph Campbell Preserves Co. discovered a way to condense and can soup and in 1900 the familiar red and white can was introduced. Their 1901 embossed tin sign of soup cans arranged to simulate the American flag remains an icon among all early advertising signs, and the highest ever sold at auction at $93,500. Unfortunately for Campbells, public sentiment toward the blatant use of the American flag to hawk your soup wasn’t well received. The company soon afterwards recalled what signs they could and had them destroyed.

6. Campbell’s Soup – in 1897 a chemist at the Joseph Campbell Preserves Co. discovered a way to condense and can soup and in 1900 the familiar red and white can was introduced. Their 1901 embossed tin sign of soup cans arranged to simulate the American flag remains an icon among all early advertising signs, and the highest ever sold at auction at $93,500. Unfortunately for Campbells, public sentiment toward the blatant use of the American flag to hawk your soup wasn’t well received. The company soon afterwards recalled what signs they could and had them destroyed.

As demand increased for pre-packaged branded products, there was a corresponding boom in advertising companies generated to garner more market share. Manufacturers began providing store merchants with posters, signs, thermometers, window displays, calendars, display cabinets & shelving, serving & change trays and every conceivable promotional giveaway imaginable that carried their product name and logo.

As demand increased for pre-packaged branded products, there was a corresponding boom in advertising companies generated to garner more market share. Manufacturers began providing store merchants with posters, signs, thermometers, window displays, calendars, display cabinets & shelving, serving & change trays and every conceivable promotional giveaway imaginable that carried their product name and logo.

Outside the store signage could be found just about everywhere. Early 19th century merchants typically had simple wood trade signs displayed above their shops, often painted with gilt lettering against a sand-paint background. Downtown streetscapes had a modest amount of outdoor advertising.

Outside the store signage could be found just about everywhere. Early 19th century merchants typically had simple wood trade signs displayed above their shops, often painted with gilt lettering against a sand-paint background. Downtown streetscapes had a modest amount of outdoor advertising.

But by the mid to late 19th century more extravagant store signage appeared featuring figural signs that left little doubt to the illiterate what could be found on the shelves inside. A 3-D mortar & pestle could be found above apothecary shops, jumbo sized bronze spectacles with glass lenses hung outside opticians shops, and oversized shoes or boots identified where cobblers and shoe shops were located. The turn of the 20th century saw some of these 3-D signs being electrified for display at night.

The mid to late 19th century also brought an explosion of advertising on formerly serene streetscapes and landscapes, especially broadsides for circus and theatre productions. Not only were they being plastered on the sides of fences and buildings in cities all over the country, but new posters were often being pasted over the competitions under the cover of nightfall.

Some companies specialized in painting outdoor advertising on everything from barns to trees and rocks. Bradbury and Houghteling were the largest national outdoor sign painters of the late 1870’s. They were responsible for the message “Use Hood’s Sarsaparilla” appearing on barns, sheds, and fences along railway lines throughout the entire country. Eventually their enormous painted advertisements on the rocks at Niagara Falls for St. Jacob’s Oil, and “Drake’s Plantation Bitters” on the cliffs of the White Mountains in New Hampshire drew enough public outcry to prompt regulation of the industry. The larger cities subsequently passed ordinances restricting and regulating the posting of broadsides and posters.

Printing Techniques for Early Advertising

In many cases, knowledge of the technique used to print the advertisement provides clues as to when it was made or even it’s authenticity. I’ll give a thumbnail sketch of the process and then talk a bit about the different types of vintage advertising products and some of their values.

– Alois Senefelder (1771-1834) was a German actor & playwright credited with the invention of lithography in 1798. In an effort to find a more economical means of publishing his plays, he discovered that greasy ink would act as a resist when drawn on the surface of a block of limestone he had been using to grind his pigments. A mild acid wash slightly etched the surface of the stone, leaving the design in relief which could then be printed onto paper with a press.

He later refined the technique so that the printing could be accomplished using a completely flat stone without etching, which he called “chemical printing” but was more commonly referred to as planographic printing. The principal at work here is that oil and water don’t mix.

The process involves drawing on a flat limestone block with greasy ink or a tusche crayon. Chemicals sensitize the areas of the stone not covered by the drawing so that they absorb water. The original grease or tusche drawing is removed but leaves a film that molecularly bonds to the stone surface that rejects water but readily accepts oily ink. The stone would be dampened with water that would be absorbed by the non-printing areas of the stone. When an oil based ink was applied with a roller, only the areas where the design had been drawn would take the ink, the rest of the stone wet from the water would repel it. Bear in mind that everything drawn on the stone had to a reverse image of the final print, including the lettering.

The process allowed artists to make prints with multiple colors using a separate stone for each color and by careful registration. A technique of “stippling” or creating tiny dots allowed amazing detail to be created on finely honed stone surfaces, while artists like Jules Cheret found that stones with more of a tooth to them provided the perfect surface for drawing broad swaths of color and texture with the tusche crayon.

By the early 1890’s printers were using large 38 ton presses and were embossing relief designs into their advertising signs. The embossing required that the paper fibers be stretched, hence long fibers found in cotton rag paper would be used. This paper was very different from wood pulp papers that contained short fibers and acids that would deteriorate the paper over time. Many of the early heavily embossed cigar labels were manufactured in this manner.

The limestone plates used in this process were extremely heavy and cumbersome. They would be 3”-4” thick and could measure from 6”x6” up to 42”x62” weighing in excess of 500 pounds – and were easily broken. Toward the end of the 19th century stone plates were being replaced by zinc plates that were far easier to handle and store.

However, neither the stone or zinc plates worked well for decorative printing on hard tin plate surfaces. Tin plates used in making signs and cans, were actually thin sheets of rolled steel that were coated by dipping in molten tin.

Two processes emerged in the late 1800’s to solve this problem. Both used an “offset” or transfer process that would transfer the design from the original printing plate to an intermediary medium that would then transfer the printed image onto the metal. This allowed for the original plate image to be drawn as a “positive” with the final print also being a “positive” image.

One process involved using a special paper coated with a rice-starch surface which would act as a “transfer paper”. All the colors of the design would be printed from “positive” plates onto the coated paper surface. The starch coating prevented the ink from soaking through into the paper fibers. When the paper prints were completed – now appearing as a reverse color image – they would be dampened and run through a press face down against a tin sign blank with a chemically sensitized surface. The final step was to dissolve the paper backer as a carrier and release the ink from the starch coating. The image would now appear as a “positive”. The printed metal signs would then be lacquered and often embossed. Edges would be rolled formed by additional steps in the case of printed tin serving trays or “self-framed” signs.

The James D. Julia auction gallery in Fairfield, ME where I work as their antique advertising consultant, recently received about 40 of these transfer printed paper signs. They’re from the Chas. W. Shonk Litho Co. in Chicago and had been handed down in the family of a gentlemen who had worked for the Shonk firm around the turn of the century. They were printed between 1895-1910, considered by many to be the “Golden Age” of lithography. All the designs would have ultimately wound up as tin advertising signage and trays. Some of these prints used a dozen or more different colors with each color requiring a separate printing plate and run through the press.

The second offset transfer process was introduced into the U.S. from Europe in the late 1800’s. It involved transferring the design from the original flat stone printing plate onto a rubber “blanket” wrapped around a roller. The rubber blanket then printed the design onto the tin surface.

Initially the rubber blankets were used with flatbed stone or zinc plates in steam powered reciprocating presses. Later it was discovered that a thinner version of the metal plate could be made which could be curved and wrapped around a cylinder. The inked metal plate would transfer the image to an intermediary rubber roller and then onto tin. Rotary offset printing was a major advancement in printing technology.

These new offset rotary presses quickly replaced the flatbed presses and became the standard for printing on paper as well. Ira Rubel, a paper manufacturer from Nutley, NJ is credited with producing the first offset rotary press for printing on paper in the U.S. in 1904.

Printers often developed their own closely guarded secret ink formulas, some containing blends of metallic powders that gave the final printed image exceptional color, depth and brilliance. Some of the lithographed paper images that came out of the Louis Prang lithography shop in Boston used up to 25 different colors for one printed image which gave the artist the ability to create richly saturated colorful images that simply can’t be duplicated by today’s modern photo-mechanical offset printing technology. It was an art form that represented the pinnacle of lithographic technology by extremely talented artists who’s highly skilled technique of creating advertising signage has long since disappeared from the American landscape.

The era from 1910-1920 ushered in photo-mechanical offset printing technology that is still in use today. Original images were photographed through “half-tone” screens and broken down into four separate plates, one for each color. This process produces a print that has rows of very fine linear dots that combined together produces a very accurate copy of the original.

With copies now able to be made directly from the original design, the lithographic artist was essentially no longer needed. Large multi-color presses were able to print massive quantities of prints in a relatively short amount of time. As the cost of production dropped dramatically, demand for the inexpensive prints grew.

Lithographers

[One of the best known early lithographers was the NYC shop of Nathanial Currier and Merritt Ives who’s business ran from 1850-1907. Although steam powered presses were available to them at the time, they preferred the quality of pulling their prints by hand. them to mass produce black and white prints which were then colored by hand, mostly by women for less than a penny apiece. They sold their small hand-colored folio prints at $.20/ea and the large folio prints between $3-5/ea.]

Chas. W. Shonk Litho Co., Chicago (1886-1935) were among the most prolific makers of tin lithographed advertising. Many of their highly skilled artists were Europeans who brought their trade with them when they immigrated. They bought the American Can Co. which was formed in 1901.

Chas. W. Shonk Litho Co., Chicago (1886-1935) were among the most prolific makers of tin lithographed advertising. Many of their highly skilled artists were Europeans who brought their trade with them when they immigrated. They bought the American Can Co. which was formed in 1901.

Coshocton, OH produced some of the finest tin advertising signs ever made due to the rivalry between two newspaper owners who became major players in the advertising business. Jasper Meek founded the Tuscarora Advertising Co. (1887-1901) and Henry Beach founded the Standard Advertising Co. (1888-1901), who’s company produced the iconic tin Campbell’s Soup American flag tin sign in 1901.They merged in 1901 as the “Meek and Beach Co.” but the partnership didn’t last long. Later that year Henry Beach sold out and formed the “H.D. Beach Co.” In 1905 Jasper Meek renamed his business the “Meek Company” (1905-1909). Soon after Meek’s retirement the company was once again renamed “American Art Works ” (1909-1950).

(It was Henry Beach’s Standard Advertising Co. that produced the iconic embossed tin Campbell’s Soup American flag sign in 1900-1901.)

Calvert Litho Co., Detroit (approx. 1878-1898)

Calvert printed a wide variety of items including circus & theatrical posters, cigar & canning labels, trade cards and produced the early Daisy Air Rifle calendars.

Kaufmann & Strauss Co., NY (1890-1970)

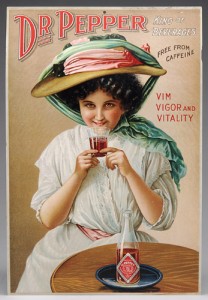

K&S were printers of early paper and tin signs for businesses around the country. They printed some of the early Dr. Pepper cardboard signs and their “El-Bart Dry Gin” tin sign recently brought $60,500 at auction.

Wolf & Co., Philadelphia, PA

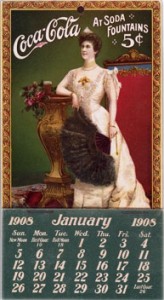

Wolf printed the very earliest Coca-Cola calendars and cardboard signs.

Niagara Litho Co., Buffalo, NY

Niagara Litho Co., Buffalo, NY

This company printed much of the 1930-40’s Coca-Cola cardboard signs. Other clients included Colgate, Canda Dry, Firestone. They also printed a wide range of WW1 posters.

Strobridge Litho Co.

The Strobridge Litho Co. has roots that go back to 1847 in Cincinnati, OH but it wasn’t until 1880 that it took on the name “Strobridge Lithographing Co.” They were a major national printer for circus, theater and movie posters that included the Ringling Bros. & Barnum & Bailey among their clients.

Donaldson Litho Co., Cincinnati, OH (1863-1987)

The Donaldson Litho Co. was officially founded in 1883 in Cincinnati, OH, moving to Newport, KY in 1898. They specialized in circus and theater poster production.

Advertising Media & Values

The variety of items used for promotional advertising is immense. I’ve attempted to identify some of the more popular forms produced and some examples of prices realized at auction.

It’s important to remember that condition is extremely critical to what an item will fetch on the auction block. A rare Coca-Cola calendar in fair condition might bring $500, whereas in mint condition it might be $5,000.

Subject matter is just as important. Generally speaking, items tend to bring stronger prices when the subject matter includes:

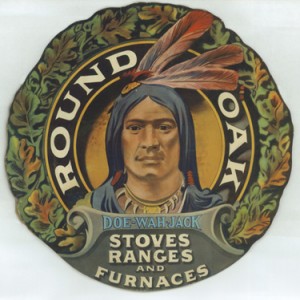

– “Old West” scenes/cowboys/cowgirls/Indians

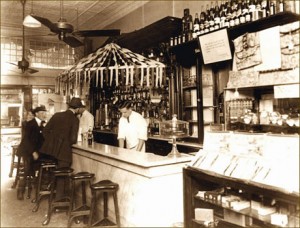

– saloon images

– attractive women; partially clad women; and did I mention partially clad women?

– attractive women; partially clad women; and did I mention partially clad women?

– strong graphics/colors (Campbell’s Soup sign)

– patriotic imagery (Uncle Sam, Lady Liberty, Stars & Stripes, etc.)

– comical images

– fanciful images (cherub riding a bumblebee; goose powered chariot)

– early sports, especially baseball

Popularity of the product is also important. Early brewery, soda and chewing gum advertising will typically sell higher than advertisements for lumber, cement, or paint for example as they tend to have a larger following of collectors.

Stock images typically bring somewhat less than designs that were custom made for the business, but this is very product driven. If a brewery used a stock image and a cement company paid a premium for custom made artwork, the brewery item will still bring more at auction every time.

The advertising company sales rep carried a binder or book with them that had an extensive selection of “stock” images. (These are known as “salesman sample books” – and can be extremely valuable.) These were far less expensive to purchase as there was only a marginal cost for printing your business name and address and/or product on top of the stock image. It’s relatively common to find the identical image on a sign, calendar or tin serving tray that was used by several different businesses.

Lastly, rarity needs to be factored into the equation. Generally, the fewer that exist, the stronger the prices are at auction. I have a colorful 1903 “Satin Skin Crème” poster that measures 26”x41” and that features an attractive young Victorian woman in fashionable attire, coyly holding a fan in her hand, with the tag line “Don’t you want a Satin Skin?”. It’s in exc. cond. and has everything going for it. But market value is less than it cost me to frame it – somewhere between $100-200 because a large pile of them were found in some warehouse years ago and they’re considered common.

Calendars

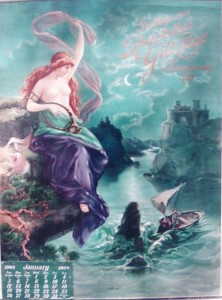

Calendars were among the best bang-for-the-buck promotional items a company would distribute. They were cheap to produce and had staying power – they were usually hung on a wall for a year with their name right on the front before being thrown away.

In the years of 1880-1900, calendars were relatively small perhaps 6”or 8” by 10” or 12”. But by the turn of the century, lithographers were producing larger more visible calendars, adorned with beautiful chromolithographed artwork. Some of these calendars were produced in tall elaborately die-cut cardboard shapes and heavily embossed, which added to their aesthetic appeal. These would have been provided by the merchant to his steady, regular customers around Christmas time. A separate paper date pad would be stapled to the bottom.

The De Laval Cream Separator Co. began producing an annual calendar beginning in 1903, that are highly collectible today. The calendar themes essentially revolved around life on the farm and carried images of children playing in bucolic countryside vistas.

– 1904 exc. cond. 2008 – $375

– 1910 exc. cond. 2006 – $1495

– 1917 exc. cond. 2008 – $575

– 1929 exc. cond. 2010 – $115

Coca-Cola’s calendars were the first to make use of celebrity spokeswomen. The famous singer and actress Hilda Clark was shown on some of their calendars and trays from 1899-1903, always enjoying a glass of Coke. She was followed by the American soprano Lillian Nordica who was used in a similar fashion for several years. The early calendars, especially from 1891-1901, are extremely scarce and can bring strong prices at auction.

– 1898 exc. cond. 2007 – $23,000

– 1899 vg cond. 2009 – $15,000

– 1899 vg cond. 2009 – $15,000

– 1912 exc. cond. 2007 – $19,500

– 1925 exc. cond. 2007 – $750

Early pre-prohibition (pre-pro) brewery calendars are very desirable. The 18th Amendment brought us Prohibition which shut down all the U.S. breweries and distilleries in 1917, until it was repealed by the 21st Amendment in 1933. Many breweries attempted to survive Prohibition by switching productioin to soft drinks or malt beverages, but a many never succeeded.

– 1914 Burkhardt Brewing Co., Akron, OH die-cut exc. cond. 2006 – $767

– 1905 Grand Rapids Brewing Co., Grand Rapids, MI die-cut exc. cond. 2007 – $3300

– 1903 Rainier Brewing Co., Seattle, WA exc. cond. 2008 – $5400

– 1908 Sacramento Brewing Co.’s Ruhstallers Beer exc. cond. – $6800

Early calendars from many of the firearm and ammunition manufactures command strong prices and are in high demand. Pre-1920 calendars from Winchester, Peters, DuPont, Remington, Hopkins & Allen, Harrington & Richardson are all desirable.

– 1908 Peters Ammunition – exc. cond. 2007 – $7,762 (JJ)

– 1898 Winchester Repeating Arms Co. – exc. cond. 2007 – $3120

– 1906 DuPont Powder – exc. cond. 2009 – $6900

– 1904 Harrington & Richardson Arms Co. – exc. cond. 2008 – $8325

– 1907 Harrington & Richardson Arms Co. – exc. cond. 2008 – $1085

And here’s one company that might surprise you as having some of the most desirable of all early firearm calendars – the Daisy Air Rifle Company.

– 1896 Daisy Air Rifle Co. – exc. cond. 2008 – $8050 (JJ)

An interesting historical footnote to the first Daisy BB gun is that it was invented by Clarence Hamilton in 1886 for the Plymouth Iron Windmill Co. of Plymouth, Michigan as a promotional premium given to every farmer who bought a windmill. It was at the time a metal and wire device that fired a lead ball with compressed air. Lewis Hough who was the president of the company at the time gave it a try and after his first shot was quoted as exclaiming in the slang of the day “Boy, that’s a daisy!” Farmers began to want the gun more than the windmill and in 1890 they produced 50,000 to keep up with demand. The gun became such a huge success that in 1895 the nearly insolvent windmill company changed its name to the Daisy Manufacturing Co., stopped making windmills and manufactured the BB guns full time.

Paper Signs & Posters

Paper signs & posters were another inexpensive way for manufacturer’s to get their name and logo into stores to create name brand recognition. The signs & posters would typically illustrate how their product could make life easier or more enjoyable for the consumer.

Some signs were shipped by manufacturers to their retail merchants, rolled up in cardboard tubes and trimmed with metal bands at the top and bottom that kept the poster flat when hung on a wall. These are usually referred to as “roll-downs” by collectors and would measure approx. 12”-15” wide x 20-28” tall.

Smaller cardboard signs would often incorporate a folding “easel” on the back so that they could be displayed on shelves or store countertops. Often these signs would have die-cut shapes to add to the visual appeal of the product. The Adams, Wrigley and Kis-Me gum companies often used die-cut women’s profiles on their easel-back signs.

Two-sided versions of these smaller signs were made intended to be hung by a string from an overhead fan in the store so that the moving air would rotate them and catch the eye of the customer. These are referred to as “fan-hangers”.

Trolley cars provided a captive audience that businesses took advantage of by printing cardboard signs that measured a standard 21” w x 11” h known as “trolley cards”. They would slip into holders located up above the passengers. Shelf life was short and when it came time to put new signs up, it was often relegated to young boys who were paid by the number of signs they replaced. They learned using a stick to push the old ones out to slip the new ones in made the work go much quicker, hence it’s not unusual to find these signs with damage. Coca-Cola was using them as early as 1905. The early ones are pricey – 1907 – $3250 in 2005; 1908 – $9300 in 2006 and 1912 – $6150.

Larger paper or cardboard signs were often framed and “lent” to the store. Salesmen would rotate old signs with new ones as they came to take new orders or re-stock. Coca-Cola developed their own signature gilt wood frames in the 1940’s to accommodate their cardboard signs now being mass produced in standard sizes. The old sign could be discarded and a new one take it’s place.

Early chromo-lithographed posters printed before photo-mechanical offset printing took over, are far more desirable and command a premium. The transition date tends to be somewhere around 1914-1918, but varies from printer to printer. After this date color images were separated into four half-tone dot screens that were combined to create the final image. The new technology resulted in much lower printing costs and faster production runs.

On occasion oversized posters were ordered that were larger than printers had the ability to make at the time on one sheet of paper. Often these would be for a circus or theatrical production and intended for display on the side of a building or billboard. In this case the printer would print the poster in multiple sheets and paste them together.

– a standard sized 1-sheet poster would measure approx. 27” x 41”

– a 2-sheet poster would measure approx. 54” x 41”

– a 4-sheet poster would measure approx. 108”x78”

– a 8-sheet poster would measure approx. 9’x7’

– a 24-sheet poster (billboard size) would measure approx. 20’wide x9’ tall Subject matter, graphics, condition, rarity and desirability drive auction values for paper and cardboard signs same, as most other forms of advertising. A few recent prices realized at auction include:

– 1905-1908 American Seal Paints 2-sheet poster w/ Uncle Sam & Lady Liberty –

42”x55” exc. cond. 2008 – $10,920 (JJ)

– ca. 1880’s Canada Southern Railway poster titled “View of Canada Southern Train Passing Niagara Falls” Colorful scene of locomotive and passenger cars in the foreground with Niagara Falls in the background. Vg. cond. 2009 – $11,500 (JJ)

– 1902 Coca-Cola paper sign with Lillian Nordica 15”x19” fair cond. 2008 – $9200

– early Daisy Air Rifles sign boy w/gun 14”x21” gd. Cond. 2009 – $7475

– ca. 1912 Old Virginia Cheroots cigar sign 16”x25” exc. cond. 2009 – $2875

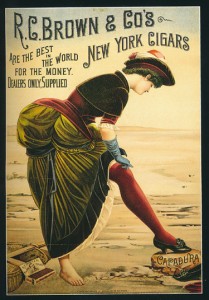

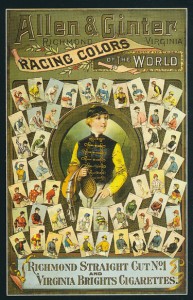

– Allen & Ginter cigarettes American Indians sign 21”x28” exc. cond. 2009 – $6325

– Buffalo Brewing Co., Sacramento, CA – topless Indian maiden riding atop a buffalo 17- 1/2”x24-1/2” exc. cond. 2008 – $47,150

– ca. 1880’s Kendall Mfg. Co., Providence, RI Soapine Soap sign w/whale – 38”x30” exc. cond. 2009 – $17,250

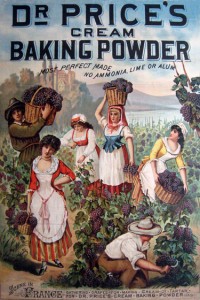

– ca.1890 Dr. Prices Baking Powder, French mountainside vineyard scene of women gathering grapes with castle in background, 18”x26” exc. cond. N/A. Dr. (Vincent Clarence) Price (1832-1914) is the movie actor Vincent Price’s grandfather who is credited with inventing the first cream of tartar baking powder first manufactured in 1869, sales of which built the family fortune. In my personal collection – only copy known.

Tin signs

Tin signs were often embossed with relief details and die-cut into distinctive shapes. “Flange” signs were produced that had one end bent at 90 degrees to mount to a wall, and extended out into the room with both sides of the sign featuring advertising. The early die-cut versions of these are especially desirable.

Tin signs were often embossed with relief details and die-cut into distinctive shapes. “Flange” signs were produced that had one end bent at 90 degrees to mount to a wall, and extended out into the room with both sides of the sign featuring advertising. The early die-cut versions of these are especially desirable.

– 1900 Coca-Cola sidewalk sign w/Hilda Clark image 20”x28” exc. cond. 2007 – $64,250

(Standard Adv.)

– ca. 1890’s Majestic Range w/ woman 25”x21” exc. cond. 2009 – $7475

– ca. 1905 Brookfield Rye Whiskey w/woman in sheer gown 23”x33” exc. cond. 2008 – $4325

– ca. 1915 Grape-Nuts w/girl & St. Bernard – exc. cond. 2007 – $3025

– ca. 1893 National Brewing Co. die-cut – vg. cond. 2009 – $9750

– ca. 1900 Harvard Brewing Co. aerial factory 40”x52” exc. cond. 2010 – $6900

– 1901 Campbell’s Soup American flag – exc. cond. 1990 – $93,500 (Standard Adv.)

– 1905 El Bart Dry Gin tin sign w/woman on beach, 33”x45” exc. cond. 2009 – $66,000

– ca. 1910 Sleepy Eye Flour w/ Indian, 20”x24” exc. cond. – $48,000

– 1890-1900 Henry Hunter Whiskey saloon scene w/cowboy 27”x36” exc. cond. 2008 – $42,000

– Buffalo Brewing Co., Sacramento, CA – Bohemian Beer charger 21” dia. exc. 2008 – $63,000.

Another unique form of tin sign found in the country store are what are referred to as “string holders”. These were the overhead holders, as opposed to countertop string holders, that held the storekeepers ball of twine used to wrap the paper parcels for customers. Often die-cut in shape, these signs had a very long shelf life in the store and were highly visible. Notable examples were made by Heinz pickles – in the form of a pickle and Red Goose Shoes – in the form of a red goose.

– ca. 1900-1910 Heinz Pickles 3-D die-cut string holder, 19”x27” vg. cond. 2008 – $8525

– ca. 1900-1910 Dutch Boy White Lead paint die-cut 2-sided string holder, 14”x27” vg. cond. 2007 – $3250

– ca. 1900-1910 Red Goose Shoes die-cut 2-sided string holder, 16”x28” vg. cond. 2007 – $2170

– 1908 Lowney’s Cocoa die-cut 2-sided string holder, 14”x24” exc. cond. 2009 – $4025

– ca. 1900-1910 Eskimo Rubbers die-cut 2-sided string holder, 13”x19” vg. 2010 – $3165

Porcelain signs

Porcelain enamel sign production began in England around 1880. In the U.S. two giants emerged that dominated the business for many years. The Baltimore Enamel Co. began in 1897 which would be the largest producer of porcelain signs in the U.S. The other company was the Enameled Iron Co. located in Beaver Falls, PA which began operations in the 1890’s and later became the Ingram-Richardson Co. in 1901. By 1920 there were hundreds of companies that emerged, with the California Metal Enameling Co., the General Porcelain Enamel & Manufacturing Co. (Veribrite) and the Tennessee Enamel Manufacturing Co. also emerging with sizable factories.

Porcelain signs are made by firing powdered glass onto iron or steel blanks. The glass is known as “frit” and is made by pouring molten glass into cold water where it would shatter into very small pieces. These pieces would then be ground down into a powder. Each color of the sign would be created by melting the appropriate color of powdered frit onto it.

Porcelain signs are made by firing powdered glass onto iron or steel blanks. The glass is known as “frit” and is made by pouring molten glass into cold water where it would shatter into very small pieces. These pieces would then be ground down into a powder. Each color of the sign would be created by melting the appropriate color of powdered frit onto it.

Early signs were made using noticeably thick iron blanks, but were replaced by steel around 1920. The metal blanks would have holes punched for hanging and then washed in an acid bath to clean them before they were then ready for the firing kiln. All signs would get an initial coat of powdered frit sprayed and fired onto them as a base coat – think of it as a primer coat in painting woodwork.

Generally signs made before 1930 would have the 1st color of powdered frit sprayed over the entire surface, on top of fired base coat. It would adhere via a static electric charge much like that seen in the small pellets that make up Styrafoam. A thin metal template would be placed over the entire sign with cut-outs where the color wasn’t desired. Using a brush, a worker would brush away the powdered frit. The template would be removed and the powdered glass left intact underneath the template would then be fired from 1700-2000 degrees and fused to the sign. This process would be repeated for each color. The end result was a sign that had a noticeable relief at the edges of the colors when felt by hand, a desirable characteristic referred to by collectors as “shelving”.

After 1930, it was discovered that silkscreening the powdered frit onto the sign reduced the amount of time it took for production. The layer of frit was thinner and after firing there was little to almost no “shelving” of the colors. The metal sign blanks themselves became thinner and porcelain gas pump signs of the late 1940’s & 50’s actually have a slight degree of flexability to them.

Early iron signs didn’t use metal grommets at the holes, but were simply punched through, resulting in what are referred to as “volcano holes” where the metal protruded on one side. Manufacturers soon realized using a press-punch and adding metal grommets to the holes would give the sign a more finished appearance and prevent the fired glass surface from chipping when displayed. All the following signs are one-sided unless indicated otherwise.

– ca. 1920-30 Gold Medal Oils automotive sign, 2-sided 30” dia. exc. cond. 2009 – $46,000

– ca. 1920-30 Red Rooster Fruit & Produce, 20” dia. exc. cond. 2007 – $8625

– ca. 1920 Munsing Wear man in unionsuit w/red robe 25”x38” exc. cond. 2004 – $4325

– ca. 1940’s Hood’s Milk w/cow’s face 30” dia. exc. cond. 2008 – $2500

– ca. 1920’s Kelly Tires 30” dia. exc. cond. 2007 – $31,200

– ca. 1930-1940 Oilzum 2-sided w/goggled driver & orange cap 20”x28” exc. 2008 – $5750

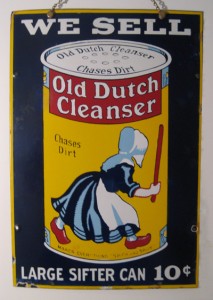

– ca. 1930’s Old Dutch Cleanser w/can of product against blue bkgd 14”x20” vg. cond. 2008 – $800 (Graphics were an early commercial design by Georgia O’keefe while living in Chicago)

Window Displays

Often companies provide large window displays to their retail customers that usually have a limited shelf life. They may be seasonal displays or intended for the holidays, but in each case pedestrian traffic notices advertising that they might otherwise not. Because they had such limited shelf life most were discarded after the season or holiday was over, lending to their rarity.

– ca. 1930 Coca-Cola Sonja Henie cardboard window display 40”x36” exc. cond. 2007 – $11,500

– 1928 Lucky Strike cardboard baseball window display with 1928 MVP’s Mickey Cochrane (AL) and Jim Bottomly (NL) found under a stairwell in a bldg. purchased by a church in 2006. Measures 66”w x 42”h exc. cond. 2006 – $34,500.

– 1940’s “The Pleasantest Place In Town” 4-pc 3-D window display of pedestrians going thru a revolving door into a diner. It was found in a log storage bin at the estate of an Arkansas family who owned the largest soda fountain in town. According to the family it had never been put on display but placed inside the bin as potential fuel. It brought just over $40,000 in 2007-JJ. Litho Niagara Litho Co., Buffalo, NY.

Most of the lithographed tin serving and change or tip trays were produced by the Chas. W. Shonk Co. in Chicago, IL or from one of the lithography companies in Coshocton, OH.

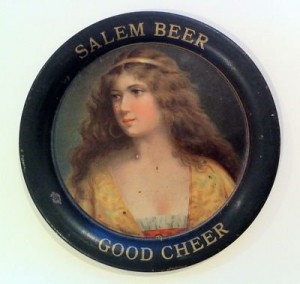

Serving and change trays were used predominately by breweries to promote their lines of ale and lager beers, and by soft drink companies to promote their flavored beverages.

Beer serving trays were usually 12-13” in diameter and are usually referred to either “pre-prohibition” produced prior to 1917, or “post-pro” meaning they were made after 1933. The smaller change or tip trays typically measure 4” in diameter, with the notable exception of those made for Coca-Cola from 1906 thru 1920 which are 4-1/4”x6” ovals. Coca-Cola made serving trays from 1897-1920 which were produced in a variety of sizes, both round and oval. Overlapping these, Coca-Cola began producing the 10-1/2”x13-1/4” rectangular tray annually from 1910 thru 1943 and then sporadically thereafter.

Here are some auction hammer prices but bear in mind that condition will have a dramatic impact on the prices listed, and will vary from sale to sale.

– 1908 Coca-Cola “topless” serving tray – 12-1/2” dia. near mint 2008 – $14,000

– 1906 Coca-Cola serving tray – 10.75”x13” exc. cond. 2008 – $10,500

– 1903 Coca-Cola serving tray – 15”x18-1/2” exc. cond. 2008 – $10,350

– 1900-05 Dr. Pepper serving tray – 13-1/2”x16-1/2” vg. cond. 2007 – $7500

– 1914 Hires Root Beer serving tray 13-1/2” dia. exc. cond. 2007 – $1090

– 1918 Zipps Cherri-O serving tray 12” dia. exc. 2008 – $800

– 1900-05 Seattle Brewing Co. Rainier Beer serving tray w/woman’s face – 13” dia. exc. 2008 – $1495

– 1909-12 National Brewing Co. National Beer serving tray w/cowboy on horse – 12- 1/2”x16” exc. 2005 – $4025

– 1910-15 Old Saratoga Whiskey serving tray w/dogs playing poker 13” dia. vg. cond. 2009 – $920

– Crowell’s Ice Cream serving tray 13-1/2” dia. exc. cond. 2007 – $1035

– 1905 Bromo Seltzer change tray 4” dia. exc. cond. 2009 – $975

– 1905 Baker’s Breakfast Cocoa change tray 6” dia. exc. cond. 2009 – $345

– 1906 De Laval Cream Separators change tray 4” dia. exc. cond. 2009 – $230

Reverse-on-glass signs

Reverse painted glass signs are another advertising medium that was popular from about 1880-1910. Because they were so time consuming to create, and therefore expensive to produce, businesses found cheaper alternatives to advertise after the turn of the century. Some are truly a work of art, incorporating silver and gold leaf or mother-of-pearl into the designs.

– ca. 1900 Buffalo Brewing Co., Sacramento, CA – Buffalo Beer sign – 38-1/2” dia. exc. cond. 2008 $54,000

– ca. 1900 Rock Island Railroad w/mother of pearl – 100”x27” exc. cond. 2009 – $34,500

– ca. 1910 Ashbury Bar corner sign for Jackson Lager, San Francisco, CA 22”x44” exc. cond. 2009 $24,150

– ca. 1900 California Brewing Co. w/bear – 16”x21” exc. 2008 – $27,600

– ca. 1890’s Yale Brewing Co., New Haven, CT w/mother of pearl – 37”x29” exc. 2008 – $2300

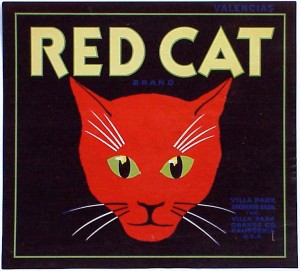

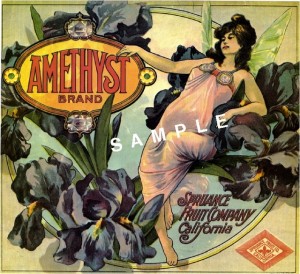

Citrus growers in California began branding their produce by placing labels on the wooden crates they shipped their fruit in, beginning around 1880 until the pre-printed cardboard box made them obsolete in the 1950’s. Many of these designs are fabulous miniature posters that deserve recognition due to the quality of their artwork, subject matter and evolution of style that reflected trends of the times. It’s estimated that in 70 years of production over 15,000 different labels were designed.

Labels were printed with every conceivable subject matter and some that were exclusive to California history: the old west, cowboys and Indians, gold mining, exotic destinations, animals, flowers, National Parks, art nouveau & deco designs, sports, etc.

When the industry abruptly switched over to the use of pre-printed cardboard boxes for shipping produce, piles of labels were left sitting on the shelves of packing plants. Today many designs, even early lithographed examples, can be bought for a few dollars apiece. Of course rare surviving copies of some of the earliest examples, often discovered in printers archive files and perhaps one of only a few known, command strong prices.

It should be pointed out that packing houses used some brand names for many years running, printing newer versions of the label every few years. Earlier versions are valued more than later ones, and in some cases there are tremendous differences in value.

– ca. 1920’s Bunny Brand orange label – 11”x10” exc. cond. – $2883

– ca. 1920’s Woodlake Nymph orange label – 11”x10” exc. cond. – $2910

– ca. 1890’s Topaz Brand orange label – 11”x10” exc. cond. – $1430

– ca. 1890’s Topaz Brand orange label – 11”x10” exc. cond. – $1430

– ca. 1930’s Santa lemon label – 12”x9”” exc. cond. – $10

– ca. 1930’s Tom Cat lemon label – 12”x9” exc. cond. – $85

– ca. 1930’s Bronco orange label – 11”x10” exc. cond. – $10

The definitive reference for anyone who has further interest is the book by Gordon McClelland and Jay Last pub. in 1985 titled “California Orange Box Labels”, Hillcrest Press. It not only is loaded with full color images of rare labels but also walks you through the different phases of artistic styles, discusses different lithography techniques that were used and provides an index of the lithography firms who produced labels.

Also, go on-line to http://content.ci.Pomona.ca.us/ and http://riversideca.gov/library/history_coll_citruslabels.asp to view the respective collections for the Pomona and Riverside, CA public libraries.

Tobacco & Cigar Labels

Just as citrus growers needed to provide brand name recognition, so did the tobacco and cigar companies. Tobacco labels were printed designed to be pasted onto the sides of tin pails that had slip-fit lids and bail handles.

– ca. 1880’s Welcome Nugget – gold miner holding large gold nugget, 7”x14” exc. cond. 2009 – $250

– ca. 1880’s The Old Sport – image of a dog dressed in suit, 10-3/4”x11” exc. cond. 2009 – $225

– ca. 1880’s Golden Eagle – eagle with American flag, 10-1/2”x10-1/4” exc. cond. 2009 – $110

Cigar labels were printed from the 1870’s thru the 1920’s and were intended to be pasted onto cigar boxes. There are two different types of labels on a cigar box. The one pasted on the lid usually measured 4”x4” and is called an “outer” label, while the other was pasted inside the lid measured 9”x6” and is referred to as an “inner” label. Many of these labels were strongly embossed in contrast to the tobacco labels.

– ca. 1880’s First Inning outer label – baseball scene, 4”x4” exc. cond. 2009 – $575

– ca. 1890’s Jack of Hearts inner label – gent w/two damsels on each arm, 8”x4-3/4” exc. cond. 2009 – $620

– ca. 1890’s Leap Frog printer’s proof inner label – woman in bathing suit leaping over frog, 7-1/4”x7” 2008 – $8625

– ca. 1890’s “7-Up” printer’s proof inner label – seven women emerging from Coney Island bathhouse in swimwear, 8”x7” exc. cond. – $4025

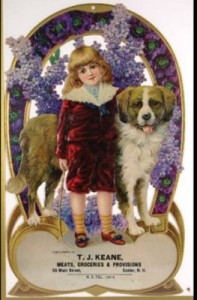

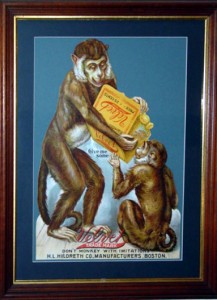

Among the more popular, inexpensive and commonly found early advertising items today are “trade cards” which were the 19th century equivalent of today’s business cards. They were miniature advertising posters – typically measuring just under 3”x5”, often printed with comical or fanciful scenes on the front – such as frogs riding bicycles or polar bears using parlor stoves – and with advertising printed on the back. Cards were printed for every imaginable product or service.

Soapine Soaps had cards with the tag line “The Dirt Killer” showing a beached whale being scrubbed so clean it removed his color. An “Ayer’s Hair Vigor” card shows a group of mermaids salvaging crates of hair product from a nearby shipwreck. Literally thousands of different images were produced.

Trade cards surged onto the scene in the 1870’s with the onset of color lithography, peaked in the 1890’s and faded away by the turn of the century when color advertising in magazines became affordable and reached a larger audience.

Advertising salesmen carried a book of stock images which they could overprint with your business name and address for a modest fee, or a custom design could be made for a premium. Product manufacturers also supplied merchants with large quantities of cards printed for their product lines. Some cards were printed in sets from 4 to 12, so to collect them all you were enticed to make multiple trips back to the store as new ones in the series were released. All these cards were handed out freely and given away with purchases. It became a national pastime in the days long before radio and TV, to collect them and place them in scrapbooks.

Many of these cards can be bought today for a few dollars, but as in all collectibles you can find some that will bring prices in the thousands. Of particular value are mechanical bank cards and clipper ship cards that promoted passenger service from the East to West coasts during the 1850’s-1880’s. Many of these ships were promoting fast passage to the newly discovered California gold fields.

– ca. 1889 “Watch Dog Safe” w/merchant overstamp – exc. cond. 2007 – $10,320

– ca. 1880’s “Darktown Battery” baseball bank w/merchant overstamp – exc. cond. 2007 $6900

– ca. 1880’s “Picture Gallery” mechanical bank w/merchant overstamp – exc. cond. 2007 $6025

– ca. 1850’s “John Tucker” clipper ship card for NY to San Francisco passenger service, 6-1/2”x4” exc. cond. 2009 – $1250

– ca. 1850’s “Eagle Wing” clipper ship card for NY to San Francisco passenger service, 6-1/2”x4” exc. cond. – $1650

– 1849 “Winged Arrow” clipper ship card for Boston to San Francisco passenger service, 3-1/4”x5-1/4” vg. cond. 2005 – $1050

Tins – Tobacco, Coffee, Talcum. Beer & Condom

A large fraternity of collectors are out there who focus just on collecting antique advertising tins.

Some of the larger early tin plate printing companies include Somers Brothers, Brooklyn, NY (1869-1920), Tin Decorating Co. Baltimore, MD (Tindeco – 1901-1944), Continental Can Co., Chicago, IL (1904-present), Norton Brothers, Chicago, IL (1868-1901) organized the American Can Co. in 1901(1901-present) by consolidating 60 tin container companies accounting for 91% of all the tin cans made in the U.S.

From 1870-1879 tins were printed in just one color on a colored base. It wasn’t until around 1882 that chromolithography was successfully used in making tin cans.

In 1935 American Can Co. introduced the first canned beer for Krueger Cream Ale which arrived in a flat top can. Later than year, Continental Can Co. introduced their “cone top” can for “Schlitz” beer. Beer can collectors are another specialized collecting fraternity that has their share of highly sought after brands and varieties.

In 1935 American Can Co. introduced the first canned beer for Krueger Cream Ale which arrived in a flat top can. Later than year, Continental Can Co. introduced their “cone top” can for “Schlitz” beer. Beer can collectors are another specialized collecting fraternity that has their share of highly sought after brands and varieties.

– ca. 1910 “Ty Cobb Tobacco” vertical pocket tin, 4-1/2” h, vg. cond. 2005 – $22,500

– ca. 1910-15 “Shogun Mixture” tobacco vertical pocket tin, 4-1/2” h, exc. cond. 2010 – $8625

– ca. 1915 “Scissors Tobacco” vertical pocket tin, 4-1/2” h, exc. cond. 2006 – $6500

– ca. 1920-30’s “Drako Coffee” 1 lb. tin, 4”x6” exc. cond. 2009 – $2300

– ca. 1920-30’s “Kamargo Coffee” 1 lb. tin, 4”x6” exc. cond. 2009 – $1840

– ca. 1920-30’s “Ben-Hur Coffee” 5-1/2”x9-1/2” exc. cond. 2009 – $1725

– ca. 1920’s “Violet Talcum Powder” tin, 4-1/2” h, exc. cond. 2009 – $575

– ca. 1920’s “Ador Me Talcum Powder” tin 5” h, exc. cond. 2005 – $275

– ca. 1920-30’s “Akron Tourist Tubes” condom tin, 1-3/4”x2-1/4”, exc. cond. 2006 – $1900

– ca. 1920-30’s “Poppy’s” condom tin, 1-3/4”x2-1/4”, exc. cond. 2006 – $1900

– ca. 1920-30’s “3-Pirates” condom tin, 1-3/4”x2-1/4”, exc. cond. 2006 – $950

– 1941 “Clipper Pale Beer” flat top can made by the Grace Brewing Co., Santa Rosa, CA, 12 oz., exc. cond. 2002 – $19,300

– 1935-42 “Royal Finest Lager Beer” 12 oz. cone top made by the Rainier Brewing Co., Seattle, WA exc. cond. 2007 – $37,501

– late 1930’s “Budweiser” crowntainer 12 oz. can, exc. cond. 2008 – $23,000

Carved wood lifesize Indians were popular trade signs for early tobacco shops. They would stand out front so that customers could readily identify where to go buy their tobacco products.

Most in good condition will sell in the range of $15,000-40,000 but much depends on the quality of the carving and it’s condition. After all, some withstood the elements and weathering for many years which would take it’s toll. If it can be attributed to a well known carver such as the Samuel Robb shop in NYC, it will bring a premium.

An amazing example just sold last month (May 2010) at auction in Texas that brought $203,150. It had been sitting in the basement of a Washington, DC home for the past 20 years. What made it remarkable was not so much the excellence of it’s carving, but that it still had it’s original poly-chromed patina surface and was in pristine condition, whereas most carvings have had multiple layers of re-paint on them with some wear and tear.

Neon Signs

Neon signs were invented in France and displayed at the 1910 Paris Exposition. They made their debut in the U.S. in 1923 at a Packard automobile dealership in Los Angeles when Earle Anthony purchased two that read simply “Packard” for $1250 each.

The outdoor neon sign was often constructed of porcelain enameled steel “cans” that housed the transformer, and could display neon tubing and advertising on one or both sides, depending on how it was being displayed.

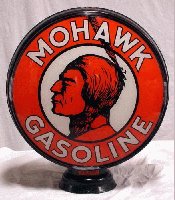

– 1930’s Mohawk Gasoline 48” dia. 1-sided exc. 2009 – $30,200

– 1930’s Mohawk Gasoline 48” dia. 1-sided exc. 2009 – $30,200

– 1930-40’s Chevrolet 2-sided 42” dia. exc. 2007 – $6000

– 1930-40’s Ford oval 2- sided 3’x6’ exc. cond. 2010 – $4800

– 1930-40’s Ford oval 2-sided 3’x6’ exc. cond. 2009 – $9600

Soda Fountain

Coca-Cola was concocted in 1886 by Atlanta, GA pharmacist John Pemberton. It evolved from modifying his original cordial formula called “Pemberton’s French Wine Coca” which combined kola nut and coca leaf extracts together with alcohol and other ingredients. The rise of the Temperance Movement convinced him to re-formulate the beverage substituting various oil extracts in lieu of the alcohol.

He took the mixture to Jacob’s Pharmacy a few doors down from where he lived, where it was combined with carbonated water and sold for 5 cents a glass as a medicinal “brain tonic” and “nerve tonic”. The name was suggested to him by his bookkeeper who also unwittingly created the flowing Spencerian script logo due to his excellent penmanship.

Pemberton died in 1888 without ever realizing the eventual success of what he had created. Another Atlanta pharmacist and businessman Asa Candler bought Pemberton’s formula in 1888 for $2300, and the rest is history.

It was Asa Candler who launched an aggressive marketing campaign that would make Coca-Cola a household word. He outfitted pharmacy soda fountains with clocks, calendars, ceramic dispensers, posters, tin signage and even leaded glass shades, all bearing the Coca-Cola name brand. They spent more on promotional advertising than any other company had in history. By 1895 he had built syrup plants in Chicago, Dallas and Los Angeles and by the turn of the century the drink was being sold across the U.S. and Canada. Coca-Cola had by this time begun selling their syrup directly to independent bottling companies around the country.

While a smart businessman, Candler never realized the potential of bottling his product for mass distribution. In 1894 a Vicksbury, MI store owner by the name of Joseph Biedenharn began bottling Coca-Cola himself in Hutchinson style bottles and selling them. He sent a case to Asa Candler who wasn’t impressed. Candler saw the money was in soda fountain sales, not bottling. The opportunity was seized on in 1899 by two attorneys Benjamin Thomas and Joseph Whitehead from Chattanooga who bought the exclusive rights to bottle and sell the beverage throughout most of the country for $1. They in turn sold bottling rights to entrepreneurs across the country. The rest is history.

Did Coca-Cola ever actually contain cocaine as an ingredient? Yes, actually it did. Which wasn’t uncommon for patent medicines of the times. The “Coca” part of the name came from the coca leaf extract, and the “Cola” part of the name was derived from the kola nut which was another principle ingredient. By the mid 1890’s public was turning against cocaine additives. Candler, worried that without any coca leaf extract in his formula he would be unable to protect the right to the name “Coca-Cola” kept a very small amount in the formula. By 1902 he had agreed to reduce the amount to 1/400th of a grain which was a mere trace. Coca-Cola contained a trace amount up until 1929 when it became totally cocaine-free.

Many people don’t realize it but there was also a Coca-Cola Chewing Gum made from 1903-1921. Asa Candler sold the naming rights to Atlanta businessmen David Carson William Clark in 1903. Sales didn’t match expectations, and starting in 1905 the company changed hands several times until Coca-Cola bought back the name and all assets and ended production in 1924.

Coca-Cola gum advertisements rank among the most valuable of all advertising signs based on size. Small cardboard die-cut signs can bring as much as $10-15,000. Even a gum wrapper brought $300 at auction in 2009.

– Leaded glass shade: vg. cond. 2009 – $5200 (JJ); vg. cond. 2008 – $6900 (JJ)

– Leaded glass shade: vg. cond. 2009 – $5200 (JJ); vg. cond. 2008 – $6900 (JJ)

– 1898 calendar, 7”x13” near mint 2007 – $20,000

– 1899 calendar, 7”x13” exc. cond. 2009 – $13,000

– 1900 tin sidewalk sign w/ Hilda Clark, 20”x28” near mint 2007 – $55,000

– 1914-16 chewing gum die-cut cardboard “Dutch Boy”, 5.5”x8” exc. cond. 2007 – $15,000

– 1893-96 Baird clock “Ideal Brain Tonic”, 26” tall exc. cond. 2005 – $12,000; 2006 – $10k;

Pepsi-Cola was invented by another pharmacist Caleb Bradham in NC in 1898 and originally sold as “Brad’s Drink”.

Dr. Pepper was created by pharmacist Charles Alderton in Morrison’s Old Corner Drug Store, Waco, TX in 1885.

Moxie originated in 1876 as a patent medicine called “Moxie Nerve Food” in Lowell, Massachusetts by Dr. Augustin Thompson, but it wasn’t until 1884 that the carbonated version was bottled and distributed.

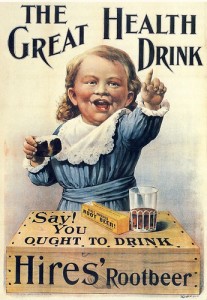

Hires Root Beer was developed in 1876 by Philadelphia pharmacist Charles Hires and debuted at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. It began to be bottled and distributed in 1893.

Hires Root Beer was developed in 1876 by Philadelphia pharmacist Charles Hires and debuted at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. It began to be bottled and distributed in 1893.

– Villeroy & Boch Mettlach stein with Ugly Kid – 4”x8.5” – 2007 – $20,000

– Villeroy & Boch Mettlach urn dispenser – 18” tall – 2007-$26k; $16,000 – 2005; $17,000 -2007

– fan pull early ver. round cardboard sign w/ “Ugly Kid” pouring drink to parched planet earth with humanized face – 11”x10” exc – 2007 – $45,000

Soda Fountain Syrup Dispensers

At the turn of the century soda fountains sold a wide variety of flavored syrups that would be mixed with carbonated water, usually for around five cents a glass. Syrup manufacturers competed with one another to come up with more eye catching syrup containers to tempt a patron into giving it a try.

– 1900-05 Hires Munimaker soda fountain marble dispenser was very heavy, made with white marble side panels and a beige marble top. A clear or milk glass globe marked with the Hires company name sits atop a silver-plated gooseneck. Measures 17”x17”x27” tall w/o the globe, 2008 – $2990 (JJ); 2008 – $2125 (JJ); 2008 – $4500

– Fan Taz ceramic baseball shaped dispenser with bat graphics, 16”h exc. 2007 – $43,000

– Jim Dandy Root Beer ceramic dispenser, 15” h exc. cond. 2005 – $40,750

– Pepsi-Cola urn shaped ceramic dispenser, 19”h exc. cond. 2005 – $31,750; exc. cond. 2007 – $29,700

– Modox ceramic dispenser w/Indian graphics, 16” h exc. cond. 2005 – $27,000

– California Iron Port ceramic dispenser, vg. cond. 2006 – $11,210

– Coca-Cola ceramic urn shaped dispenser, exc. cond. 2007 – $8,800

Trade Signs

Trade signs were often simple flat wood signs with a moulded border and painted in a two-tone color scheme. More elaborate trade signs were figural and intended to convey what goods the store sold inside.

Trade signs were often simple flat wood signs with a moulded border and painted in a two-tone color scheme. More elaborate trade signs were figural and intended to convey what goods the store sold inside.

Tavern signs are among the earliest of all trade signs and often because of their historical significance tend to bring very strong prices. They tended to carry the name of the tavern and/or the name of the proprietor as well.

– ca. 1890 The Alaska Fur Co. carved gilt wood, orig. surface, 2-sided, 53”x55” 2007- $79,000

– ca. 1880’s dentist trade sign – entire carved upper set teeth, 17”x18” – 2007 – $44,000

– 18th century wood tavern sign for “T. Doty”, Canton, MA. 51”x44” 2008 – $28,440

– 1802 wood American tavern sign for “R. Estabrooks” tavern with anchor graphic, 2006

– $81,200

– ca. 1880’s “Acorn Stoves and Ranges” figural 2-sided embossed metal acorn shaped sign, 40”x50” 2009- $7500

– 1890’s apothecary mortar & pestle, 22”x36”leaded glass w/glass “jewels” exc. cond. 2006 – $28,320

Store Display Cabinets

These cabinets would have a hinged front door with an embossed tin lithographed panel insert. The interiors are fitted up with eggcrate shelving for holding product. Some have a tin panel or cardboard insert in a 2nd rear door.

– ca. 1910 Dr. Lesures Veterinary Remedies w/horsehead tin front, 27” h 2005 – $3250; 2009 – $22k mint

– ca. 1900 Dr. Daniels Veterinary Medicines w/Dr. Daniel himself, 20”x29” exc. 2006- $3500; 2006-$3250;

– ca. Pratts Veterinary w/blue tin panel list of remedies, 34” h – 2006 – $1700

– ca. 1890 Diamond Dyes – “Fairy” – 31”h – near mint – 2005 – $3000

– ca. 1910 Diamond Dyes – “Balloon” – 15”w x24” h – $750-1500

– ca. 1910-1914 Diamond Dyes – “Mansion” – 15”w x24” h – $750-1500

– ca. 1906 Diamond Dyes – “Governess” – 30” h – $750-1500

– ca. 1890 Diamond Dyes – “Jester” – 27” h – $750-1500

Spool Cabinets

There are dozens of different forms from about twenty different manufactures.

– ca. 1890 Corticelli fancy w/ clock – $3200

– ca. 1900 Merricks w/ tambour doors/2-curved glass panels; ave. $2000; $1100

– ca. 1900 Merricks round glass like spool – $2400; $1700; $1300; $1000

– ca. 1910 Brooks – blue glass fronts – $800-1000

– ca. 1890 Belding Bros. – tall w/ gallery & mirror – $2000

– ca. 1910 Clark’s – 6 drwr ruby red drwr fronts – $1000-1500

Salesman Samples

Salesman often went on the road taking with them miniature examples of large or heavy products they were selling to shop merchants. A full size barbershop chair for example simply wasn’t practical to lug around to retail barber establishments, so companies like Koken’s in St. Louis, MO manufactured a 16” tall miniature version. Their miniature is an exact replica of the original, complete in every detail right down to working hydraulics, leather upholstery, porcelain arm rests and nickel plated articulating foot and head rests – no expense was spared.

Because so few salesman’s samples were made and even fewer survived, they are an eagerly sought after collectible. Those examples that have cross-over interest to the antique advertising/country store collector command a premium.

– ca. 1900 Koken’s barber chair, Koken Co., St. Louis, MO – red/brown leather upholstery, white porcelain armrests, nickel plated trim/foot rest/head rest – 16” tall. 1999 exc. cond. – $48,875 (JJ); 2006 exc. cond. – $27,000; 2008 exc. cond. – $11,500 & $29,000

– 1895 Koken’s barber chair, Koken Co., St. Louis, MO – rare carved wood version with black leather trim, working hydraulics, nickel plated trim & foot rests, exc. cond. 1999 – $51,750 (JJ)

– 1929 model Coca-Cola double-Glascock cooler w/miniature crate of bottles, 10.5”wx13”h – $8500

– 1939 model Coca-Cola cooler w/leather case – 9” tall exc. 2007 – $5500

– ca. 1900 collapsing country store wood baker’s shelf, 12” tall exc. cond. 2004 – $4675

– ca. 1909 Hires Root Beer “Munimaker” soda fountain dispenser. The “Holy Grail” of all salesman’s samples. A perfect miniature in marble with silver plated gooseneck and milk glass globe, it came housed in a velvet lined black leather case and stands 12” tall. The Thunell collection 1999, exc. cond. – $77,000 (so if you’ve got a spare one or two of these lying around why don’t you give me a call); also 2007 exc. w/o case – $55,000

In 1906 the Pure Food and Drug Act was enacted to protect consumers from food and drugs that might be potentially dangers and/or addictive. It required disclosure of any alcohol or narcotic ingredients on the packaging and stated that “the label shall embody no statement which shall be false or misleading in any particular”.

The ripple effect on manufacturer’s advertising claims was significant. Coca-Cola no longer mentioned that it “Cure headaches”, “Relieves exhaustion” and was a “Brain tonic” in their advertising. The same was true for many patent medicine companies. Some scrambled to reformulate their products while others didn’t – they simply complied with the new law and listed their ingredients on the label. After all, the law didn’t forbid patent medicines from containing alcohol or narcotics, it merely said the label has to disclose what’s in it. So the odds are pretty good that if the advertising sign you have says that it cures diphtheria, scurvy, malaria is a swell brain tonic, that it was produced prior to 1907.

Heroin was introduced in 1898 as a cure for morphine addiction if you can believe that. In the early 1900’s the philanthropic Saint James Society in the U.S. mounted a campaign to supply free samples of heroin through the mail to morphine addicts who are trying give up their habits. This didn’t quite work out as they had planned.

Here are a few turn of the century products that were popular with consumers:

– Bayer marketed heroin over-the-counter as a cough suppressant from 1898 to 1910. I would think that might work!

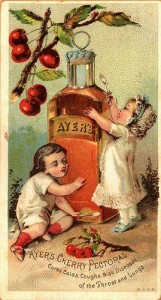

– “Ayers Cherry Pectoral” made in Lowell, MA (1841-1945) distributed trade cards and posters that often featured young children. It was hawked as “curing colds, coughs and all diseases”. But depending what year you bought it, it contained either morphine or heroin.

– “Ayers Cherry Pectoral” made in Lowell, MA (1841-1945) distributed trade cards and posters that often featured young children. It was hawked as “curing colds, coughs and all diseases”. But depending what year you bought it, it contained either morphine or heroin.

– “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup For Children” began production in Bangor, ME in 1849 and was hugely successful perhaps in part because it contained 1 grain (65 mg) of morphine per fluid ounce and alcohol. That should keep the rug-rats quiet for a while.

– Up until the 1914 Harrison Act was passed, cocaine was sold over the counter. Even Pope Leo XIII was endorsing “Vin Mariani Wine Tonic” in their advertising, which was oaded with cocaine at the time. He went as far as awarding Angelo Mariani, the producer, with a Vatican gold medal. “You just know with a name like “Wine of Coca” that it’s got to be good.”

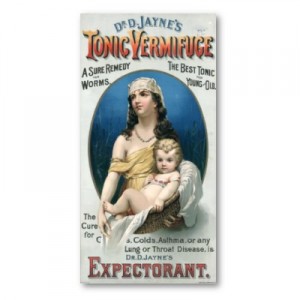

– “Dr. D. Jayne’s Expectorant” descended from a line of clergymen in Philadelphia, PA in the mid-1800’s and contained opium right up until 1919. Praise the Lord!

– “Dr. D. Jayne’s Expectorant” descended from a line of clergymen in Philadelphia, PA in the mid-1800’s and contained opium right up until 1919. Praise the Lord!