As Stated in a Speech given by Jeff Wichmann of American Bottle Auctions, August 7, 2010.

Click here for our podcast with Jeff.

At the FOHBC conference in Wilmington, Ohio.

Did you know that in the 1970’s bottle collecting was one of the most popular hobbies in America? Yep. Right up there with stamps and coins. But of course bottle collecting started much earlier than that. Let’s take a look.

Did you know that in the 1970’s bottle collecting was one of the most popular hobbies in America? Yep. Right up there with stamps and coins. But of course bottle collecting started much earlier than that. Let’s take a look.

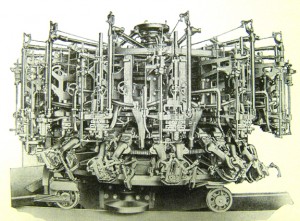

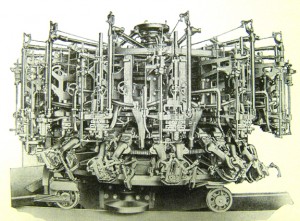

Did you know that Andrew Carnegie and Henry Ford collected old bottles? As early as 1900, Edwin A. Barber wrote American Glassware. To our knowledge it is the first reference that dealt solely with the subject of American Glass. By 1914 Frederick William Hunter wrote Stiegel Glass which also looked at the Wistars and their association with glass in America. In 1920 American Bottles Old & New by William S. Walbridge was published out of Toledo, Ohio. His book was interesting, Walbridge’s idea of new was the invention of the fifteen-arm bottle making machine. He points out it weighed 100,000 pounds and had an increased production capacity over the first commercial machine of 202%. A picture of this new fangled equipment reminds one more of a Terminator movie than bottles. He also points out that in the year 1916, the production of the entire Owens owned plants for the year amounted to 613,959,696 bottles. A lofty number even by today’s standards.

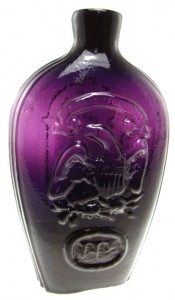

Soon came Early American Bottles and Flasks by Stephen Van Rensselaer in 1921 and a Revised Version in 1926. Here was a book that set a new level for books on the subject for years to come. Van Rensselaer was the first to chronicle bottles by category. He had 26 groups, which were divided into definitive categories based on their embossed patterns. It was a boon to collectors of the day, and the fuel that would fire what was to come. Van Rensselaer was considered the leading expert on glass as his exhaustive efforts not only cataloged most of the known examples, but also showed pictures of each one. It was a Herculean effort that was to be the mainstay of the bottle-collecting world.

Soon came Early American Bottles and Flasks by Stephen Van Rensselaer in 1921 and a Revised Version in 1926. Here was a book that set a new level for books on the subject for years to come. Van Rensselaer was the first to chronicle bottles by category. He had 26 groups, which were divided into definitive categories based on their embossed patterns. It was a boon to collectors of the day, and the fuel that would fire what was to come. Van Rensselaer was considered the leading expert on glass as his exhaustive efforts not only cataloged most of the known examples, but also showed pictures of each one. It was a Herculean effort that was to be the mainstay of the bottle-collecting world.

Another early contributor was a man named Harry Hall White who wrote a series of articles on Kentucky Glass Works and early Pittsburgh glasshouses in a magazine called Antiques in 1926. He was to write articles for Antique over the next 15 years on everything from excavations at Mantua to Coventry Glass Works in Connecticut. When talking American glass, one must not forget a woman named Rhea Mansfield Knittle who in 1924 wrote an article named Muskingham County, Ohio, Glass, which was two years before the contributions of White. She delivered another five articles for Antique and then a very popular book called Early American Glass, published in 1927. Interestingly, another book written by a woman named Mary Harrod Northend entitled, American Glass, was published a year earlier. In it, she discussed everything from Sandwich to Wistarberg. It contained plates of some very rare pieces including what she calls “The Famous “Booz” Bottle,” in light green no less. Although her name is not mentioned in many of the books I’ve researched, surely she was a major contributor in her day. In her preface she writes, “The story of glass is in reality one that has never been fully told, but it has been my endeavor to keep close to the spirit of the times so that he who reads may learn of its evolution which finally ended in acknowledged success.” Boy, if she were around today. What Northend would ultimately find out is how plastic is now largely the future of glass.

Glass by the Metropolitan Museum of Art came out in 1936. It was a compilation of the history of glass making throughout the world. It starts in Egypt with the first recorded evidence of glass making in 3200 B.C. Meanwhile Ruth Webb Lee’s Sandwich Glass Handbook done in 1939 began her lifelong love affair with Sandwich Glass. The series of Barlow/Kaiser books on the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company in Massachusetts was to come later and although Lee’s efforts were groundbreaking, the new contributions of Barlow/Kaiser included beautiful photographs and an incredible source of information for those interested in Sandwich glass. Early American Glass-the Magnificent Collection Formed by the late William T.H. Howe of Cincinnati, Ohio was published in 1940 and was one of the first published auction catalogs of strictly bottles and glass. It included “so-called Stiegel and Ohio techniques in all of the available colors,” and “Blown Three-Mold technique in pressed glass are also to be found in a rich assortment of patterns and colors. Furthermore, the group of historical flasks contains many of the most highly prized specimens.” This collection came with much help from George S. McKearin, generally thought to be one of the founding fathers of the hobby. Today an offering such as the Howe collection would be considered an almost impossible task. Outside of the very top collectors in the world, few could offer such an amazing array of early bottles and flasks.

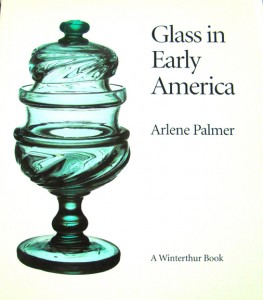

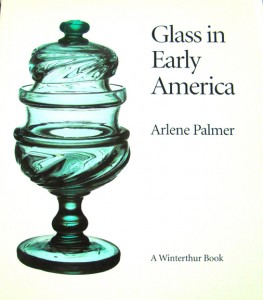

Early American Bottles and Flasks Collected by the Late Alfred B. Maclay written in 1945 came next, offering an amazing display of bottles for auction. The catalog is hard bound and contains mostly historical flasks. Many are extremely rare and no doubt some are on collector’s shelves today. In 1947 a book about a specific area of collecting appeared in the form of Bitters Bottles by J.H. Thompson. He choose to concentrate on one area and even as early as the 1947, you could see a pattern evolving, the rare and valuable versus the more common examples we still differentiate today. American Glass by Valentine VanTassel appeared in 1950. His attempt at chronicling the history of glass in the United States was worthy of any research collection and as I’ve seen numerous copies of the book, it must have been fairly well received. It includes a number of black and white prints including a picture of the Harrison Hard Cider flask produced in 1840. American Historical Flasks by Helen McKearin was the first of her hobby changing efforts in 1953 with more, much more to come. Arlene Palmer’s Glass in Early America started using full-color along with black and white pictures which brought the  photography of bottles and glass to a new level. The remarkable photographs are still right up there with some of the finest ever done. Palmer’s book is regarded as one of the most concise and well-written books ever published on early American glass and is still a mainstay in the collecting world.

photography of bottles and glass to a new level. The remarkable photographs are still right up there with some of the finest ever done. Palmer’s book is regarded as one of the most concise and well-written books ever published on early American glass and is still a mainstay in the collecting world.

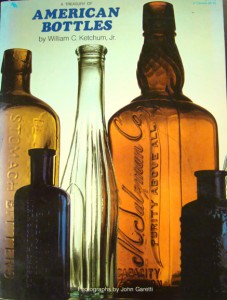

Bitters Bottles by Richard Watson appeared in 1965, another important addition which focused on one particular area of this newly evolving hobby. While Thompson had the first book on bitters, Watson was able to expand the category with newly found information. A Treasury of American Bottles by William Ketchum in 1975 was again one of the first books to fully utilize full-color pictures and with the presentation of much of the Burt Spiller collection, is still considered a major addition to the hobby. In 1978 the bottle and glass world was soon to change forever with the publishing of the newest and most up to date version of American Bottles and Flasks and Their Ancestry by Helen McKearin and Kenneth M. Wilson. Together, Wilson and McKearin produced not only the most thorough and concise assemblage of information ever seen in one book; they also developed the classification system for flasks and bottles that is still in use today. The book originally appeared in 1948 and was reprinted again as late as 1989. By our estimations it is the most reprinted book of it’s type ever written. So from Edwin Barber’s American Glassware to the bible of bottles and glass in the McKearin/Wilson effort, collectors had a much larger volume of information and form of reference than ever before. There are many other books out there we fail to mention here due to space, but it’s estimated by our count that there are over 500 books that have been written on the subject.

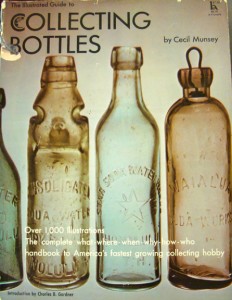

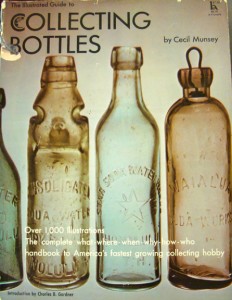

So if one were to look at the books printed up to this point, especially the early contributions, they all had one thing in common, the words “Early,” and “American.” But one needed only to glance westward as the hobby had already gained a head of steam on the Pacific Coast. The first recognized bottle club was actually started in Sacramento, California by John Tibbitts during the mid 1960’s. It was called The Antique Bottle Collectors Association, which later became the Federation of Historic Bottle Collectors or FOHBC. Tibbits had been writing a newsletter he called Chips from the Pontil and eventually it turned into a book in 1967 called John Doe Bottle Collector. Chips from the Pontil was published from 1959 to 68. Tibbits also wrote a book, How To Collect Antique Bottles in 1969. By the 1970’s, the bottle fever had started out west in a big way. Collecting Bottles by Cecil Munsey came out in 1970. This 308-page effort contained loads of great photographs and drawings with a well-constructed history of bottles and glass. The Muncie work was one of the firsts to lay out the history from beginning to end and it is still a terrific book for anyone interested in the hobby. Grace Kendrick had already written a book called The Antique Bottle Collector in 1963 out of Nevada. Bob and Pat Ferraro, also from Nevada wrote A Bottle Collectors Book in 1966 along with The Past in Glass soon thereafter. Both Kendrick and the Ferraro’s were from Nevada which was picking up a great deal of steam in it’s own right. Many, many bottles were shipped to Nevada from San Francisco and it became a breeding ground for collectors eager to find western glass.

So if one were to look at the books printed up to this point, especially the early contributions, they all had one thing in common, the words “Early,” and “American.” But one needed only to glance westward as the hobby had already gained a head of steam on the Pacific Coast. The first recognized bottle club was actually started in Sacramento, California by John Tibbitts during the mid 1960’s. It was called The Antique Bottle Collectors Association, which later became the Federation of Historic Bottle Collectors or FOHBC. Tibbits had been writing a newsletter he called Chips from the Pontil and eventually it turned into a book in 1967 called John Doe Bottle Collector. Chips from the Pontil was published from 1959 to 68. Tibbits also wrote a book, How To Collect Antique Bottles in 1969. By the 1970’s, the bottle fever had started out west in a big way. Collecting Bottles by Cecil Munsey came out in 1970. This 308-page effort contained loads of great photographs and drawings with a well-constructed history of bottles and glass. The Muncie work was one of the firsts to lay out the history from beginning to end and it is still a terrific book for anyone interested in the hobby. Grace Kendrick had already written a book called The Antique Bottle Collector in 1963 out of Nevada. Bob and Pat Ferraro, also from Nevada wrote A Bottle Collectors Book in 1966 along with The Past in Glass soon thereafter. Both Kendrick and the Ferraro’s were from Nevada which was picking up a great deal of steam in it’s own right. Many, many bottles were shipped to Nevada from San Francisco and it became a breeding ground for collectors eager to find western glass.

Peck and his wife Audie Markota wrote Western Blob Top Soda and Mineral Water Bottles in the 1970’s. Still the definitive reference on western blob sodas. John Thomas wrote Whiskey Bottles of the Old West in 1969 and he also wrote a number of other related books in the years that followed. Thomas virtually created the demand for western whiskey fifths and flasks. His efforts started an excitement among collectors that still lives on today. His expertise in bottle hunting and ability to write and draw pictures of virtually every western whiskey bottle and flask was monumental in securing the future of whiskey collectors in the west. You could say he gave spirit to those who collected spirit bottles. Betty (Wilson) Zumwalt wrote Spirit Bottles of the Old West in 1968 along with Western Bitters 1n 1969 and 19th Century Medicine in Glass in 1971. Zumwalt was soon to write the definitive book on pickle and sauce bottles in an aptly named book, Ketchup, Pickles and Sauces 19th Century Food In Glass. Her work was along with Thomas and Markota the foundation for the huge upsurge in collecting western bottles. Byron and Vicky Martin wrote Here’s to Beers, still the bible for beer bottle collectors despite the efforts of a number of other beer collectors writings, many of which are valuable contributions. The Martin book was primarily on western beer bottles. Doug Leybourne wrote The Red Book of Fruit Jars which is also considered the bible for fruit jar collectors. Bitters Bottles by Carolyn Ring and later in conjunction with Bill Ham would be considered the must have of bitters bottles books along with it’s supplement. Ring especially, developed the reference system used for bitters bottles today. A specific bitters book focusing on just western bitters bottles also appeared in the form of Antique Western Bitters Bottles written by this author in 1999. Like the Thomas whiskey book or the Zumwalt medicine book, here was a bitters book dealing with a particular geographical area of collecting a particular type of bottle. It was just one of the many books written for a specific type of western made or distributed bottles to come.

Peck and his wife Audie Markota wrote Western Blob Top Soda and Mineral Water Bottles in the 1970’s. Still the definitive reference on western blob sodas. John Thomas wrote Whiskey Bottles of the Old West in 1969 and he also wrote a number of other related books in the years that followed. Thomas virtually created the demand for western whiskey fifths and flasks. His efforts started an excitement among collectors that still lives on today. His expertise in bottle hunting and ability to write and draw pictures of virtually every western whiskey bottle and flask was monumental in securing the future of whiskey collectors in the west. You could say he gave spirit to those who collected spirit bottles. Betty (Wilson) Zumwalt wrote Spirit Bottles of the Old West in 1968 along with Western Bitters 1n 1969 and 19th Century Medicine in Glass in 1971. Zumwalt was soon to write the definitive book on pickle and sauce bottles in an aptly named book, Ketchup, Pickles and Sauces 19th Century Food In Glass. Her work was along with Thomas and Markota the foundation for the huge upsurge in collecting western bottles. Byron and Vicky Martin wrote Here’s to Beers, still the bible for beer bottle collectors despite the efforts of a number of other beer collectors writings, many of which are valuable contributions. The Martin book was primarily on western beer bottles. Doug Leybourne wrote The Red Book of Fruit Jars which is also considered the bible for fruit jar collectors. Bitters Bottles by Carolyn Ring and later in conjunction with Bill Ham would be considered the must have of bitters bottles books along with it’s supplement. Ring especially, developed the reference system used for bitters bottles today. A specific bitters book focusing on just western bitters bottles also appeared in the form of Antique Western Bitters Bottles written by this author in 1999. Like the Thomas whiskey book or the Zumwalt medicine book, here was a bitters book dealing with a particular geographical area of collecting a particular type of bottle. It was just one of the many books written for a specific type of western made or distributed bottles to come.

So at this point, we had almost as many books written for the western bottle scene as we did for the east. Granted, the works of Ferraro or Tibbits may not have been the masterpieces of Arlene Palmer or Helen McKearin, but there weren’t the number of bottles to discuss in a western book not to mention the glasshouses and overall history. The first glasshouse in the west didn’t occur until 1859, however in the east that would have been just a few years too late. It is believed the first glass made in America was by the Wistarburgh Glass Manufactory in 1738. Established by Caspar Wistar in Southern New Jersey, it lasted for 40 years. So you had quite a jump on western glass production in the east and you had a lot more people that needed bottles. So lots more production, earlier bottles and hence the classic “Early American” glass, collectors strive so hard to find. That doesn’t mean that bottles made in the west or for the west can’t compete in their own right. When I say in the west or for the west, there are a couple schools of thought regarding this. If a bottle was made after 1859 out west specifically San Francisco, it was without question a western bottle. But some bottles were made in Ohio, New York and other eastern glasshouses that were made specifically for the west. They were only distributed in the west and are generally considered western.

Soda or mineral water bottles are a good example. The earliest and most prized examples were made in the east during the 1850’s and 60’s. Since many have the name San Francisco, Sacramento or even Shasta on them, they are collected by western collectors as western bottles. Even bottles that don’t have a town name but are only found in the west are considered western. Some of these include the Catawba Wine Bitters, the Wister’s Club House Gin, and the Bryant’s Bitters. Bottle collecting then is pretty much divided up into east and west, some collect western bottles and some collect eastern bottles. Sometime a collector will go after both. But generally we’ve found that western and eastern collectors are pretty much into the bottles made on which side of the country they live in. Bitters bottles could be the one exception.

So we now had a very well thought out, bevy of bottle books that were giving people new insight into the hobby in a way that hadn’t happened before. For good reason, the 1970’s ushered in a new era of bottle collecting.  It was a nationwide event when Charles Gardner, a well-known collector of his day sold his collection in 1975. Of course the popularity of bottles meant one more thing, just what were these bottles worth?

It was a nationwide event when Charles Gardner, a well-known collector of his day sold his collection in 1975. Of course the popularity of bottles meant one more thing, just what were these bottles worth?

In the late 1950’s, early 60’s, there was a guy named Bruce Scott who collected lunch boxes. He had a house full of them and decided to write a book about lunch boxes and he entitled it simply enough, The 50’s and 60’s Lunchbox. In it, he included prices based on the number of particular boxes he had seen and pretty much had his way creating a book which essentially was written about his own collection. How did it go? Well, once people discovered a lunch box was actually collectible, there was really only one place to turn to get more information. The Bruce Scott book took off and soon people were digging through their garages and basements looking for their hidden treasure. Lunch boxes began to become popular, his modest investment in lunch boxes was soon worth a fortune and he’s still selling books today. The point of the story is that here we have a guy who just happened to like collecting lunch boxes. He then went on to not only write a book, but also created a whole new area of collecting. He was the lunch box market and he could put any price he wanted on any lunch box. So he took what was essentially nothing and virtually created a new hobby.

So now we move on to the 1980’s. In the 1960’s bottles were easier to get; their appeal was based mainly on their looks. As time went on, books came out and the hobby established prices. Rarity became clearer, we were able to create a base on which to value bottles. I hear many stories of people trading a valuable bottle for a common one, not knowing the Tippecano they traded for a green Old Sachem’s bitters would later turned out to be a disaster. Collectors in the early years were simply basing their decision on pure aesthetics. Minor chips, dings? They didn’t become a big deal until people started putting out big money for them. As a friend of mine, Ken Salazar recently said, “when I started digging for bottles I didn’t know they were even worth money.” In addition, we were soon to learn about the so-called 20-year cycle in collecting. So what happened in the 80’s? Well, although we had a load of collectors, they didn’t have a real means to talk to each other. Oh there were telephones, people bought and sold bottles through the mail. There were guys like Bob Barnett who wrote a price guide on whiskey bottles called Western Whiskey Bottles. He sent out a monthly list of bottles for sale. There were bottle shows but they were scattered and infrequent and in essence there wasn’t the ability to converse with other collectors in a national way. There was no real highway of information. No way in which collectors could easily share their finds and discuss bottles in general. Sure, bottles were still very popular, there was a bottle magazine, you could write letters and call people but it wasn’t like the burst of enthusiasm we saw in the 60’s and 70’s. So we had the excitement, discovery and all-out interest from the 70’s waning in the 1980’s. Was Bottle collecting beginning to suffer from the 20-year cycle?

It’s known that in collecting, there is a period where something will become very popular and then lose that popularity. Beanie Babies are a good example, but it happens with almost every area of collecting. A generation is considered 40 years but it takes time and experience to appreciate some collectibles. So let’s say you collected stamps at age 30 and you eagerly sought out better and better examples and went to stamp shows and basically immersed yourself in stamps for 20 years and now you’re 50. You decide that stamps are neat, but you just can’t devote the time you once did and decide to sell them. So Bill decides to sell his collection and another stamp collector named Fred does the same. They’ve gone up in value and it’s time to take a break, sell the collection and even possibly start collecting something else. When a number of people do this, you do two things, you lose a buyer and you make the availability of stamps more plentiful. If you have 10 collectors of something and five decide to sell, you are left with a huge influx of those items and less people to buy them. A number of factors begin to occur, more stamps, less interest, less buyers. This 20-year rule or cycle isn’t in stone, it can change in both time and duration, sometimes it’s 30 years or like the Beanie Babies craze in 1995 through 2000, just five years. But as you look through the history of collecting, lulls in the hobby happen in just about every area of collecting.

From experience we know that people collect things that other people want. It’s rare that you find the lone lunch box collector but rather more often people who collect things that are more mainstream, allowing them to meet and share their collections. In our auctions for instance, a piece may sit there for a week in a 10-day auction. Finally someone puts in a bid and next thing you know there are five people bidding on the item. It’s that, “if he wants it I want it,” syndrome. Have you ever noticed that when maybe you’re at a bottle show and there’s a bottle you want and you walk around thinking about it and you finally decide to go back and make an offer and it’s gone? Now you really want it and most likely so do a few other people that couldn’t pull the trigger. The “I want it if you want it” syndrome also works the other way. Sometimes we’ll have a person buy a bottle and return it or simply not pay for it. We will call the underbidder who just a week before had to have it but was outbid at the last minute. We explain to them that their bid is now the top bid and the item is theirs. “No thanks,” we hear more often than not. “I’ve purchased something else,” or “well, I think I’ve changed my mind,” is the general mindset. If they don’t want it why would I want it? It’s the “if he doesn’t want it, I don’t want it,” syndrome.

So as people were spreading the word about bottles in the 60’s and 70’s, towards the end of the 70’s and into the early 80’s we saw a bit of a lull.  If you look around, you don’t see many books being published on bottles in the 80’s, there was that communication problem and interest slowed. It wasn’t earth shattering, it rarely is, but it’s a sign that there just wasn’t the interest that there was 10 years prior. Looking back, it was a great time to load up. Some collectors did and are smiling all the way to the bank. Others sold off their collections, only to wish later they’d sat on their green Sachem’s or yellow Indian Queen. Bottles were still a fairly strong collectible, you just didn’t have the enthusiasm you saw earlier. Of course there are other factors that can affect certain areas of collecting. Economic unrest, a lack of items in that collecting circle, infighting among the leading collectors, there is a myriad of reasons for the checks and balance system in collecting. For Beanie Babies it was over production, it was the same with baseball cards in the late 1980’s and 90’s. In addition, with Beanie Babies they were new, they had no real history to speak of, they were just a phenomena. Ty Warner, the company that gave birth to these babies knew the magic words in collecting, people want what others want. Their main strategy was to offer their products in very limited editions. People ate it up. Collectors wanted Beanie Babies and it was only because others did also. Once people looked around and came to their senses, they realized how ridiculous it was paying hundreds of dollars for a brand new toy just because it was one of only five hundred made. Try selling a dark blue Peanut the Elephant these days. A recent search on Ebay revealed hundreds of the Ty Warner Beanie Babies offered for as low as 25 cents apiece with no bids.

If you look around, you don’t see many books being published on bottles in the 80’s, there was that communication problem and interest slowed. It wasn’t earth shattering, it rarely is, but it’s a sign that there just wasn’t the interest that there was 10 years prior. Looking back, it was a great time to load up. Some collectors did and are smiling all the way to the bank. Others sold off their collections, only to wish later they’d sat on their green Sachem’s or yellow Indian Queen. Bottles were still a fairly strong collectible, you just didn’t have the enthusiasm you saw earlier. Of course there are other factors that can affect certain areas of collecting. Economic unrest, a lack of items in that collecting circle, infighting among the leading collectors, there is a myriad of reasons for the checks and balance system in collecting. For Beanie Babies it was over production, it was the same with baseball cards in the late 1980’s and 90’s. In addition, with Beanie Babies they were new, they had no real history to speak of, they were just a phenomena. Ty Warner, the company that gave birth to these babies knew the magic words in collecting, people want what others want. Their main strategy was to offer their products in very limited editions. People ate it up. Collectors wanted Beanie Babies and it was only because others did also. Once people looked around and came to their senses, they realized how ridiculous it was paying hundreds of dollars for a brand new toy just because it was one of only five hundred made. Try selling a dark blue Peanut the Elephant these days. A recent search on Ebay revealed hundreds of the Ty Warner Beanie Babies offered for as low as 25 cents apiece with no bids.

As the new decade arrived, so did the ability to spread the word about bottles. Websites sprang up and there was the beginning of national auctions like Skinners and Glass Works Auctions. Out west we had Western Glass Auctions, these were auctions that were selling specifically antique bottles and glass. Also, people like Ralph and Terry Kovel had been publishing a newsletter and were now producing books on bottles along with other numerous books on antiques. They even had their own television show. Terry Kovel still is an internationally known syndicated columnist with her Kovel’s Corner appearing in newspapers across the country and around the world. Terry and her late husband’s contribution to collecting in America has led the way in fulfilling generations of Americans thirst for collecting. The American version of The Antiques Roadshow, which began in 1996, generated a new interest in antiques. But maybe the most important event was Ebay, which started in 1995. Ebay was now a major player in the selling of everything from buttons to bottles. So out from the closets came the current collectors but in addition you had new people taking a look at bottles as a collectible. The beauty of antique bottles was again gaining momentum. Bottle had become more definitive. We now knew that particular bottles were rare and others weren’t. As time went on, we saw more books. The hobby was back on track and as we headed into the new century, bottle collecting was very strong. We had a way to convey our information. The computer was making the hobby more accessible to everyone. The hobby seemed secure and strong. But just how strong was it?

Today we have collectors from all over the world collecting bottles and glass. Collectors are learning more and more about bottles everyday. There are now hundreds of websites devoted to bottle collecting. With self-publishing there are a number of books being written on very specific areas of collecting. I counted close to 30 books that I have on my shelf that have been written in the last few years alone. More auction houses have sprung up. Ironically, Ebay, who some could argue really got the thing started has now taken a back seat to live auctions. It would seem however, that by all accounts, bottle collecting is now thriving. But for every step forward the hobby makes, it seems to take a step back. We have a federation, which meets on a regular basis, but just what they actually accomplish is more of a question mark than brick and mortar. A series of fakes appeared years ago and seem to pop up now and again. Bottle shows just aren’t what they used to be. People used to spend days preparing their displays in anticipation of winning a blue ribbon. These days it’s a much less eager effort accomplished by the few who still care to spend the time to present bottles in grand fashion. Why travel to a bottle show in Keene, New Hampshire when you could sit in your pajamas at home and purchase bottles online? In my mind there is nothing that compares to attending a bottle show. You can’t replace the personal examination of a bottle and the excitement of meeting friends old and new at a bottle show with cruising the Internet. You can’t go to all the shows but it’s really the best way to learn more. With the ammunition you’ve gleaned from books and the Internet, a bottle show is the final piece of the puzzle, a wonderland of glass, all there for your inspection. For more information on shows in your area, check out our website or the FOHBC site. There are numerous online sites that will give you the information you need.

Today we have collectors from all over the world collecting bottles and glass. Collectors are learning more and more about bottles everyday. There are now hundreds of websites devoted to bottle collecting. With self-publishing there are a number of books being written on very specific areas of collecting. I counted close to 30 books that I have on my shelf that have been written in the last few years alone. More auction houses have sprung up. Ironically, Ebay, who some could argue really got the thing started has now taken a back seat to live auctions. It would seem however, that by all accounts, bottle collecting is now thriving. But for every step forward the hobby makes, it seems to take a step back. We have a federation, which meets on a regular basis, but just what they actually accomplish is more of a question mark than brick and mortar. A series of fakes appeared years ago and seem to pop up now and again. Bottle shows just aren’t what they used to be. People used to spend days preparing their displays in anticipation of winning a blue ribbon. These days it’s a much less eager effort accomplished by the few who still care to spend the time to present bottles in grand fashion. Why travel to a bottle show in Keene, New Hampshire when you could sit in your pajamas at home and purchase bottles online? In my mind there is nothing that compares to attending a bottle show. You can’t replace the personal examination of a bottle and the excitement of meeting friends old and new at a bottle show with cruising the Internet. You can’t go to all the shows but it’s really the best way to learn more. With the ammunition you’ve gleaned from books and the Internet, a bottle show is the final piece of the puzzle, a wonderland of glass, all there for your inspection. For more information on shows in your area, check out our website or the FOHBC site. There are numerous online sites that will give you the information you need.

As in any hobby, once categories are defined, rarity established and collectors become knowledgeable about the hobby, the prices are going to escalate. The important word here is knowledge. Like the lunch box phenomena, we now have a roadmap of what is what. With the present day bottle collector, what they are learning or have the capacity to learn has never been greater. So where is the hobby today in terms of popularity in comparison to other hobbies? Is this the beginning of the end or the beginning of the beginning? Are we heading into a new 20-year down or up cycle? The last 20 years haven’t been all butterflies and jelly beans. We’ve had some ups and downs but a somewhat steady progression in general. Certainly some areas of collecting has slowed, others hastened but it seems in just the last few years, or more specifically this year, we’ve seen some staggering prices paid for some bottles. Is this current year of 2010 the signal of the beginning? The start of the beginning of a new age in bottle collecting?

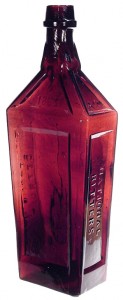

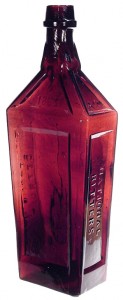

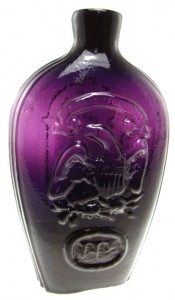

The year 2010 was and is a great year for the bottle-collecting hobby. As I write this in September, I look back at some of the transactions that occurred and see a new perspective creeping in on the horizon. Consider these bargains; a blue Homestead Bitters sold privately for $200,000, a blue firecracker GI-14 flask set a new world’s auction record selling for $100,000 at a Norm Heckler sale. A purple Masonic GIV-1 brought $75,000 in a private sale. A Druids Bitters in green, $50,000. A GII-69 yellow and olive Eagle/Cornucopia, brought $44,850. These are just a few of the bottles that sold at never before seen prices. A recent article printed in Maine Antique Digest included some observations on the state of the bottle hobby from the Norman Heckler camp. It read, “In the end, it is not simply the record prices but the overall strength of the bottle and flask market that is most impressive. While other categories have floundered in the so-called downturn, bottle and flask prices have never wavered, and with an ever-increasing crop of buyers, the future for the category is rosy.” When asked the reason for the resurgence, Heckler pointed out simply, “new blood.”

When you think about bottles compared to art for instance, what is the difference? In many cases they’re both old, they are beautiful to look at and often both have historical significance. Neither of them will drive you to work or cook you dinner, but really, there’s not a lot of difference; except in price. Not value, price. If an Andy Warhol self-portrait sells for $32.56 million dollars as it did in a recent Sotheby’s auction, what is so darn crazy about $200,000 for a one known Homestead Bitters in blue? A Jasper Johns painting of a flag entitled oddly enough “Flag” sold for $28.6 million recently at a Christie’s auction. And $100,000 is too much for a blue GI-14 firecracker? A mechanical bank called “Breadwinnners,” just brought $94,000 in a RSL auction in Maryland. Baseball cards and memorabilia? A Mickey Mantle game used jersey just sold for $125,000 in a recent SCP auction in Southern California. One of a number of Mantle jerseys. To obtain the truly rare Honus Wagner T-206 baseball card in a grade 8, plan on paying around $2.8 million, if you can find one. A bargain for sure. But you can buy a much lesser grade example for around a million. As far as practical collecting, there’s some to be found. But people generally collect things that give them visceral entertainment or possibly memories of the past. Cars you can at least drive. A Boston and Sandwich candlestick can light your room with a candle in it. Guns you can target practice with or an old book you can read. Photography gives us insight into the past, memories again, with records you can listen to music. With furniture you can sit down and eat dinner at an old Stickley dining table. A collectible watch will tell you the time. Many of these collectibles fit into the “memory” category. But most of the collectibles today that bring the highest dollar value have beauty, which lies in the eye of the collector. Art is the most expensive, stamps and jewelry can get up there, too. A Batman comic book just did $400,000 at auction. Coins, they can be made of gold but you will most likely be paying a lot more than the real gold value of the coin.

When you think about it, it’s the beauty of the world, those alluring, captivating images, textures and charmingly presented items that light up our eyes, that strike a nerve in the beauty center of our brain that captures our greatest attention. Whether it be a Monet painting or a green Fish Bitters. $75,000 for a purple Masonic GIV-1 might seem like a ton of money but it’s one of only a few known. Show me a stamp or coin that costs the same amount and there might be 50 known. So clearly the comparison to rare bottles and rare stamps or coins and many other collectibles just hasn’t caught up yet. And of course art has no bounds. As you’ve seen, art is in a category of it’s own.

When you think about it, it’s the beauty of the world, those alluring, captivating images, textures and charmingly presented items that light up our eyes, that strike a nerve in the beauty center of our brain that captures our greatest attention. Whether it be a Monet painting or a green Fish Bitters. $75,000 for a purple Masonic GIV-1 might seem like a ton of money but it’s one of only a few known. Show me a stamp or coin that costs the same amount and there might be 50 known. So clearly the comparison to rare bottles and rare stamps or coins and many other collectibles just hasn’t caught up yet. And of course art has no bounds. As you’ve seen, art is in a category of it’s own.

So, the current state of the bottle hobby is in good shape from what I’ve seen. Average bottles sell for average prices, probably more than ten years ago. But they sell. Certain bottles have increased in price. Some areas of bottle collecting has slowed, but generally across the board it’s been pretty strong. It’s the rarest of the rare however that has taken a huge upswing over the past year or two. It’s difficult to ascertain the value of bottles; it’s almost a little depressing. What’s it worth I am constantly asked. I have friends that feel the hobby is becoming a money hobby, the innocence lost. Why does everything have to have a price tag? Well, I ask them, what’s the one question they ask you on the Antiques Roadshow when they’re through looking at the object? What’s it worth? Like it or not, there’s always going to be the price element in collecting, anything. From old cigar boxes to Rolex watches. You can’t get away from it. Some bottles don’t cost a lot and that’s great. You can put together a wonderful, colorful collection for a relatively cheap amount. But like most collecting, as you continue to learn, knowledge and experience brings you to understand the finer examples and it becomes a lot about money. Remember that it’s the knowledge and experience. That isn’t to say you can’t collect beautiful average valued bottles your whole life, but experience tells me as one grows, a Volkswagen bug just ain’t gonna cut it anymore when you see your friends moving up to a new Audi or Mercedes.

You can only hope to predict the future by learning from the past. If we are nearing the end you’ll know it. The end starts with a decline in interest. For whatever reason, the number of people involved in the hobby declines, people start selling their collections and there is a flood of sellers and prices begin to decline. Try selling even the rarest of the Beanie Babies today. Good luck. It can also happen gradually like after the 1970’s. Don’t forget the 20-year rule. You need that new influx of collectors to sustain a hobby. Most likely what’s going to happen isn’t any different than what happens with any area of collecting. Things will ebb and flow. Some bottles will go up and some will come down. But overall, it’s all up to us to keep the hobby growing. People don’t live forever and new blood is essential.

Click here for American Bottle Auctions’ website. Click here for our podcast with Jeff.